Arts and GH Heritage

Cornell Scholar Traces Her Akan Roots as She Connects Ghana–Côte d’Ivoire Cultural Ties: ‘The Border Was Not Drawn by Us’

A moment of cultural resonance unfolded at the United Nations this week, when renowned Ivorian academic Professor N’Dri Thérèse Assié-Lumumba spoke passionately about her deep ancestral links to Ghana.

She recounted how Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire share a common heritage that predates the colonial borders separating West African nations today.

The distinguished scholar, a Professor of Africana Studies at Cornell University, was featured in a conversation hosted by Ghanaian diplomat and veteran journalist Ben Dotse Malor during the 2025 Academic Conference on Africa.

The event, organised by the UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa (OSAA), ran from Monday to Wednesday.

Malor introduced Assié-Lumumba with a playful observation: she looked unmistakably Ghanaian, specifically Akan or Asante, despite holding Ivorian nationality.

The professor confirmed the connection with a personal revelation: her grandmother once lived in Kumasi, Ghana’s cultural heartland.

The Border Was Not Drawn by Us

Assié-Lumumba used the moment to revisit a familiar truth across the continent: that colonial borders fractured long-standing political and cultural bonds.

“Well, as you know, the border was not dropped by us,” she said. “The Europeans had a project to break down strong political unity so that they would remain there.”

Her own name carries that continuity. In both Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, “Assié” means down, earth or land—a linguistic bridge that mirrors historical migrations of Akan-related groups, including the Baule people in present-day Côte d’Ivoire.

Sankofa and the African Renaissance

During her conference presentation, Assié-Lumumba invoked Sankofa, the iconic Akan symbol of a bird looking backward while moving forward. She explained that its message—returning to the past to inform the future—captures the essence of Africa’s ongoing quest for renewal.

“Sankofa is our renaissance,” she said. “The idea is not to go back, but to look back—to learn, to understand where you were, where you have been, and how you got to where you are. Only then can you strategically plan for the future.”

The professor further noted that many European scholars misunderstand the symbol, assuming it advocates regression. Instead, she noted, Sankofa expresses continuity, analysis, and intentional progress.

Her latest book, Akwaba Africa: African Renaissance in the 21st Century, draws from that same philosophy. While “akwaba” is widely known to mean “welcome,” she clarified that the deeper etymology is “welcome back”—a call to restoration and revival.

Real Histories, Shared Futures

Assié-Lumumba also offered a quick lesson in 18th-century political history, recounting a succession crisis following the death of Osei Tutu, an event that led some Akan groups, including her ancestors, to migrate westward.

Her grandmother’s later life in Kumasi, the second largest city in Ghana, brings the story full circle.

The exchange at UN Headquarters is enriching because it echoed an ongoing conversation across West Africa: cultural identity does not end at national borders. From language and spirituality to arts and governance systems, the Akan world, stretching from Ghana to Côte d’Ivoire, remains deeply interwoven.

At a time when Africa is redefining its global standing, scholars like Assié-Lumumba are urging nations to look backward with intention and forward with clarity.

Sankofa, in her telling, is not nostalgia—it is strategy!

Arts and GH Heritage

Threads of Memory, Strokes of Now: A Guide to Ghana’s Living Art Scene

If you’ve ever stood far from home and felt a tug at the sound of a talking drum or the sight of woven colour, Ghana’s art scene will feel like a quiet homecoming.

The art world in Ghana is not usually behind white walls. It lives in courtyards, roadside workshops, coastal galleries and northern warehouses, many of which are rooted in memory, restless with new ideas. For those in the diaspora searching for connection beyond genealogy charts, Ghana’s arts and crafts offer something tactile, human, and deeply familiar.

Where It All Begins: Art as Language, Not Ornament

Long before galleries and residencies, art in Ghana was a way of speaking. Cloth, symbols, beads, wood and clay carried meaning—status, philosophy, faith, resistance. That legacy still shapes the country’s creative pulse today. What makes Ghana compelling is how effortlessly the old and the new share space. Tradition here adapts, questions, and sometimes argues with the present.

Accra: The Capital of Constant Reinvention

Start in Accra, where the art scene mirrors the city itself—layered, loud, reflective.

Near Independence Square, the Art Centre in Accra hums with movement. This isn’t a museum experience; it’s a conversation. Carvers shape masks in real time, traders argue prices with humour, and every stall tells a story of lineage and labour. It’s the first place where art feels less like display and more like family business.

A quieter but no less powerful stop is the Nubuke Foundation.

Set away from the city’s rush, it offers space to think. Exhibitions here are thoughtful, sometimes unsettling, often intimate—perfect for anyone curious about how Ghanaian artists are interrogating identity, migration, and memory.

The Ano Institute of Arts and Knowledge

Just a short drive away, the Ano Institute of Arts and Knowledge deepens the experience. Part archive, part exhibition space, Ano invites visitors to slow down and listen to oral histories, visual essays, and stories that don’t always make it into textbooks.

Gallery 1957

For a polished counterpoint, Gallery 1957, tucked inside the Kempinski Hotel Gold Coast City, presents African contemporary art with global confidence. Its where Ghanaian creativity meets the international art circuit, without losing its grounding.

Artists Alliance Gallery

Along the coast, the Artists Alliance Gallery feels expansive in every sense. Three floors of paintings, sculpture, and traditional objects unfold like a visual archive of West African creativity—ideal for anyone wanting breadth and depth in one visit.

Art Africa Gallery

And in East Legon, Art Africa Gallery offers an intimate encounter with works that speak across generations, blending the past with present-day realities.

Kumasi and the Ashanti Heartland

Leaving the coast for Kumasi is like stepping into the spiritual engine room of Ghanaian art. The Art Centre in Kumasi showcases mastery in wood, clay and textile traditions that have shaped Ghana’s visual language for centuries.

Bonwire Kente

Just outside the city lies Bonwire, where Kente is not fashion but inheritance. Watching the weavers work is a reminder that skill is memory passed hand to hand—something no factory can replicate.

Northern Ghana: Art as Architecture and Activism

In Tamale, the Red Clay Studio reshapes what an art space can be. Created by Ibrahim Mahama, it fuses installation, architecture, and community life. Here, art doesn’t just comment on society; it builds within it.

Why This Matters

To walk through Ghana’s art spaces is to confront questions many in the diaspora carry quietly: What did we inherit? What was interrupted? What can still be reclaimed? These galleries and craft centres don’t offer neat answers—but they offer something better: dialogue.

Ghana’s art scene isn’t asking to be admired from a distance. It invites touch, debate, memory, and return. And for anyone tracing their way back—culturally, creatively, or emotionally—it offers a map drawn not in ink, but in clay, cloth, wood, and bold new ideas.

Arts and GH Heritage

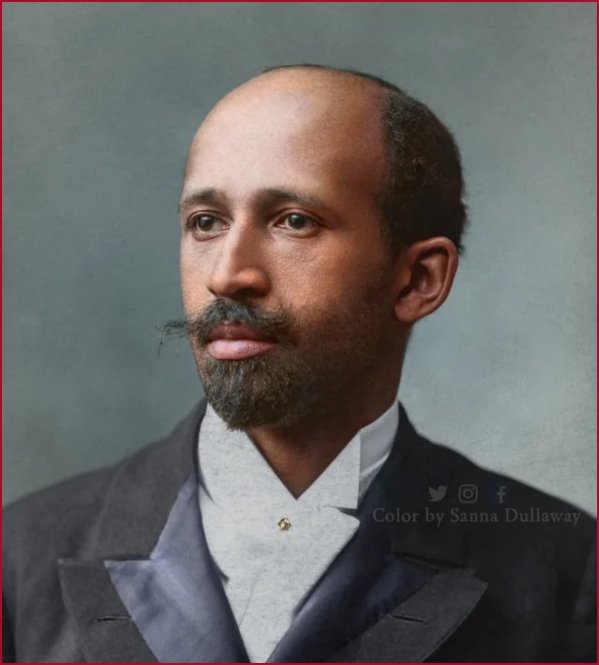

W.E.B. Du Bois’ Ghana Exile: Why America’s Reject Became Africa’s Historian

The house at No. 22 First Circular Road in Cantonments is quiet now. Bougainvillea spills over the perimeter wall. The grounds, as visitors often note, possess a “tranquil beauty” that seems deliberately removed from the clamor of Accra’s traffic-choked arteries.

It is here, in this unassuming bungalow, that William Edward Burghardt Du Bois spent the final two years of his life. It is here that he died, on August 27, 1963, at the age of 95. And it is here, in a marble mausoleum behind the house, that he and his wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, are interred.

But for the thousands of African American tourists who have made pilgrimage to this site since Ghana’s 2019 Year of Return campaign, the Du Bois Centre represents something far more complex than a grave. It is the physical manifestation of a question that haunts the Black American encounter with Ghana: What does it mean to be embraced by a country that your own rejected?

“We didn’t really get to know him,” one Black American traveler, visiting the Centre with a heritage tour group, recently remarked. “He was a hero to Black America, but not necessarily to white America. And while you’re going through that museum, you get to see why.”

The observation, captured in a travel vlog from a retired military couple’s first trip to Ghana, cuts to the heart of Du Bois’ American erasure—and Ghanaian reclamation.

The Scholar and the Stateless

By the time Du Bois arrived in Accra in 1961, he had already lived several lifetimes. He was the first Black American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard. He was a founder of the NAACP and the editor of The Crisis for a quarter-century. He had published 21 books, organized five Pan-African Congresses, and established himself as the preeminent Black intellectual of the 20th century.

He was also, at 93, a man without a country.

The United States government, in the throes of Cold War anti-communist hysteria, had refused to renew his passport. Du Bois had been indicted in 1951 as an unregistered foreign agent for his peace activism; though acquitted, he remained under FBI surveillance and was effectively barred from international travel.

“Hounded by the U.S. government and marginalized by the academic and policy establishments that once welcomed him,” writes historian Zachariah Mampilly, “Du Bois was fleeing his homeland. It was a figurative exile that turned literal when the U.S. State Department refused to renew his passport, rendering him functionally stateless.”

Enter Kwame Nkrumah.

Ghana’s first president, then three years into his experiment in independent African governance, extended an invitation: Come to Accra. Direct the Encyclopedia Africana. Help us document, for the first time, the history and civilization of the African people.

Du Bois accepted. He did not renounce his American citizenship, but he became a citizen of Ghana—a symbolic act of repatriation that Nkrumah understood as both political and profoundly personal.

The Project That Remains Unfinished

The Encyclopedia Africana was Du Bois’ final intellectual obsession. Conceived as a corrective to centuries of European scholarship that denied Africa its own history, the project aimed to produce a comprehensive, multi-volume record of African life and achievement “from the standpoint of Africa and peoples of African descent”.

Du Bois drafted the proposal in Brooklyn in October 1960, outlining the terms for Ghanaian government involvement and support. He arrived in Accra the following year, set up his library in the Cantonments bungalow, and began recruiting contributors.

But the work moved slowly. Du Bois was frail. The resources were modest. And the vision was staggering in its ambition.

He died 23 months after arriving, his great project incomplete.

“He spent the next two years in Ghana, where local and international activists and thinkers embraced him warmly, but he made little progress,” Mampilly notes . The Encyclopedia Africana would not be published until 1999—and then only in a partial, pilot edition.

Yet the failure to complete the encyclopedia may be less significant than the fact that Ghana invited him to attempt it at all.

From Neglect to Reclamation

For decades after Du Bois’ death, the Cantonments bungalow existed in a state of suspended animation. Opened as a public memorial in 1985 under President Jerry John Rawlings, the Centre housed his personal library, his papers, and his grave. But funding was erratic. Maintenance was deferred. By the 2010s, visitors reported books “slowly decomposing in the heat” and a general atmosphere of benign neglect.

“It’s hard to argue that Du Bois is underrecognized,” Mampilly writes. “Despite the acclaim, however, Du Bois remains underappreciated”.

The Year of Return changed that calculus.

In 2019, President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo visited New York and announced a historic partnership with the W.E.B. Du Bois Museum Foundation. The goal: transform the neglected memorial into a “state-of-the-art museum complex and world-class destination for scholars and heritage tourists”.

Designed by Sir David Adjaye—the celebrated Ghanaian-British architect behind the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington—the new complex will feature a library, reading room, event hall, outdoor auditorium, amphitheater, lecture space, and a guest house for visiting scholars. The refurbished bungalow will remain, preserved as it was when Du Bois lived and worked there.

The projected cost: between $50 million and $70 million.

“This agreement will build on the government’s ‘Year of Return’ and ‘Beyond the Return’ campaigns that encourage the return of the African diaspora from around the world,” Akufo-Addo said at the 2021 signing ceremony. He urged African Americans to “follow in the footsteps of W.E.B. Du Bois by making Africa their home and contributing to the development of the continent.”

Pilgrimage and Pedagogy

For Black American visitors, the Du Bois Centre now functions as both shrine and classroom.

Japhet Aryiku, executive director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Museum Foundation, was himself inspired at a young age by Du Bois’ writings. A Ghanaian-American with more than four decades in corporate America, Aryiku describes the redevelopment project as a form of ancestral repatriation—not of bodies, but of legacy.

“All the money that we are going to invest in here, there is no money going back anywhere,” Aryiku said at the Centre’s 40th anniversary celebration in 2025. “It is not a loan. It is a grant.”

That same year, the African American Association of Ghana marked Juneteenth with a parade from the Du Bois Centre to the Accra Tourist Information Centre—a deliberate routing that positioned Du Bois’ grave as the symbolic starting point for Black America’s emancipation commemoration.

Maurice Cheetham, vice-president of the association, emphasized the educational imperative. The goal, he said, was “to educate Ghanaians about the history and significance of Juneteenth, which is not widely known in the country.” But implicit in the event was a parallel education for African American participants: the lesson that Ghana had embraced a man America had cast out.

The Irony of Return

There is a profound irony embedded in the Du Bois pilgrimage, one that many visitors only fully grasp when they stand before his grave.

Du Bois came to Ghana because he was not welcome in the United States. He was denied a passport, surveilled by his own government, and effectively exiled from the country of his birth. He did not choose repatriation as a leisure pursuit; he chose it as a survival strategy.

Yet today, the very infrastructure of diaspora tourism—the flights, the hotels, the heritage itineraries, the naming ceremonies—depends on framing Ghana as a site of voluntary return.

“Welcome home,” the airport greeters say. “You have come back to your ancestral land.”

Du Bois never heard those words at Kotoka International Airport. When he arrived in 1961, there was no Year of Return, no Beyond the Return, no state-sponsored campaign to lure the diaspora home. There was only Nkrumah’s invitation and the quiet desperation of a 93-year-old man who had outlived his country’s tolerance.

That his final residence has now become the central pilgrimage site for the very tourism industry his exile helped inspire is not lost on those who visit.

“This trip is more than just travel,” the retired military veteran reflected in her vlog. “It was for us. It was a reconnection with our roots.”

Her husband, standing beside her at the Du Bois Centre, added:

“We didn’t know anything about him. But it’s a beautiful museum, and we got the chance to see what you’re thinking about when you’re doing those things.”

The Future of the Legacy

The new Du Bois Museum Complex is expected to open within the next three to five years, transforming what was once a neglected memorial into what the government promises will be “a premier global institution and heritage site.”

Jeffrey Du Bois Peck, the great-grandson of W.E.B. and Shirley Graham Du Bois, has pledged his commitment to preserving his ancestors’ legacy. At the 40th anniversary celebration, he stood alongside Ghanaian officials and foundation executives, a living link between the scholar who arrived in 1961 and the diaspora tourists who now arrive by the thousands.

Whether the new complex can resolve the tensions inherent in Du Bois’ story—between exile and return, between American rejection and Ghanaian embrace, between unfinished scholarship and completed pilgrimage—remains an open question.

But perhaps that is not the measure of success.

The Centre’s current condition, as described by one visitor, includes “numerous original photographs” of Du Bois alongside images of Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, Nkrumah, and Martin Luther King Jr. There are photos of his friendship with Mao Tse-Tung and his visits to China. His subterranean bath, built so the 93-year-old could enter it without difficulty, remains intact.

These are the artifacts of a life lived across continents, across movements, across the shifting boundaries of belonging and exile. They do not resolve into a single narrative. They accumulate, like the bougainvillea on the perimeter wall, covering the hard edges with persistent, flowering life.

And every Saturday, behind the house where Du Bois died, a farmers’ market operates. Vendors sell fresh local foods, products, clothes, jewelry. Tourists wander through, posing for selfies.

It is not the Encyclopedia Africana that Du Bois envisioned. But it is, perhaps, something he would have recognized: the ordinary, enduring commerce of a people reclaiming their own story.

Arts and GH Heritage

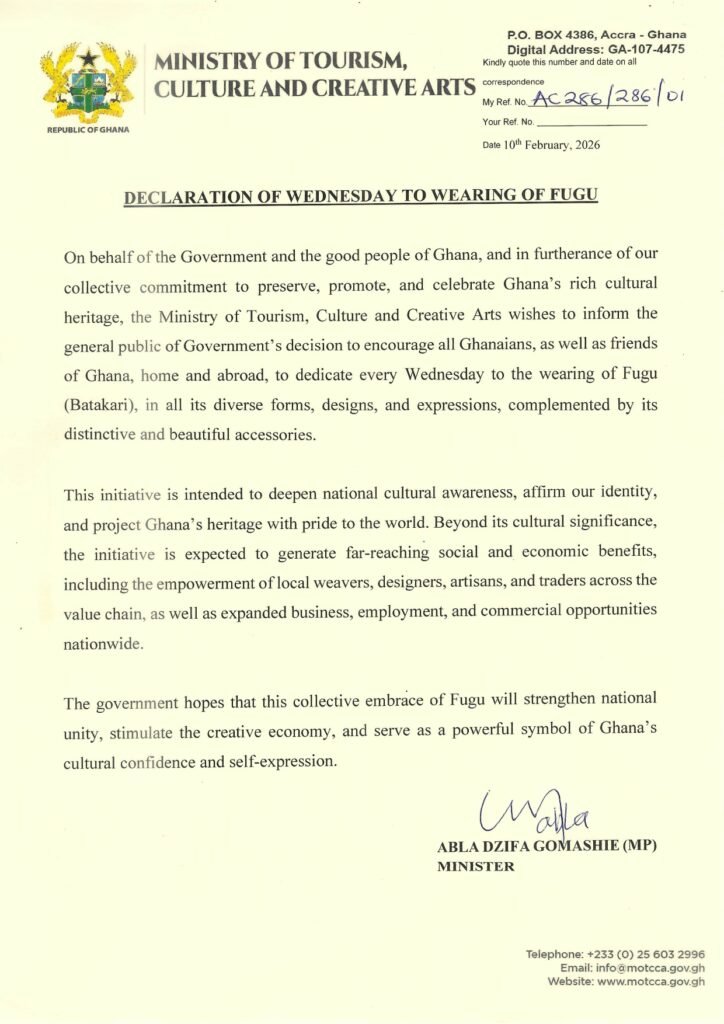

Zambia, Thank You! Ghana Declares National Fugu Day After Viral Smock Row

A new Ghana government directive is poised to formally integrate the popular traditional Ghanaian attire, Fugu, into the nation’s weekly fashion cycle.

The Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Creative Arts has announced the designation of every Wednesday for the wearing of Fugu (Batakari), in a move that will directly influence the personal style choices of citizens and residents.

In a statement dated February 10, 2026, the Ministry declared the initiative to “encourage all Ghanaians, as well as friends of Ghana, home and abroad, to dedicate every Wednesday to the wearing of Fugu (Batakari), in all its diverse forms, designs, and expressions, complemented by its distinctive and beautiful accessories.”

The policy is part of the government’s efforts to:

“Deepen national cultural awareness, affirm our identity, and project Ghana’s heritage with pride to the world.”

By formalizing a specific day for its wear, the Fugu—a smock with origins in northern Ghana known for its intricate hand-embroidery and symbolic patterns—is elevated from ceremonial and occasional wear to a staple of the weekly wardrobe.

The statement highlights the garment’s “diverse forms, designs, and expressions,” indicating an expectation for widespread and creative adaptation of the traditional style for modern, daily wear. This regularizes a visible, collective display of cultural attire across offices, markets, schools, and social settings every week.

Furthermore, the Ministry directly linked the fashion directive to economic stimulation for the domestic creative industry.

The initiative is intended to generate “far-reaching social and economic benefits, including the empowerment of local weavers, designers, artisans, and traders across the value chain.”

By creating a consistent, high-demand cycle for the garment, the policy aims to “strengthen national unity, stimulate the creative economy, and serve as a powerful symbol of Ghana’s cultural confidence and self-expression.”

The directive, signed by the sector Minister, Abla Dzifa Gomashie (MP), is effective immediately, inviting a nationwide shift in sartorial practice every midweek.

How Zambia Helped Propel a Popular Local Fashion into a Powerful Cultural Moment

Following a row on social media, nicknamed “Blouse Gate,” erupted when some Zambian users on X mocked President Mahama’s elegant Fugu smock—calling it a “blouse” or maternity dress, Ghanaians responded with pride, flooding timelines with photos of the hand-woven garment worn by warriors, kings, and independence heroes like Kwame Nkrumah.

Many Ghanaians, home and abroad, also countered by sharing images of Zambia’s own Lozi traditional attire (the Siziba skirt), playfully asking:

“How can you call our smock a blouse when your men rock full skirts?”

The exchange could have escalated, but Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema stepped in with grace and humor. He publicly praised the Fugu, expressed admiration for its craftsmanship, and announced he would personally order more for himself and others. By this time, images of even non-Ghanaians in Europe, Asia and the Americas wearing Fugu had inundated social media.

The move by the Zambian leader instantly shifted the narrative from mockery to mutual respect. Zambia Revenue Authority even scrapped import duties and taxes on a single Fugu for personal use, signaling official acceptance and boosting cultural exchange.

President Mahama, who wore the Fugu to the UN General Assembly in 2025 without similar attention, welcomed the global spotlight. He gifted one to President Hichilema and noted the economic boost for smock sellers. The visa-free travel agreement signed during the visit further strengthened ties, turning a fashion spat into a bridge between West and Southern Africa.

Now, with the declaration of “Fugu Wednesday,” Ghanaians will wear the smock proudly, celebrate Ghanaian identity, and promote local textile artisans.

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana News Live Updates: Catch up on all the Breaking News Today (Feb. 15, 2026)

-

Ghana News13 hours ago

Ghana News13 hours agoGhana News Live Updates: Catch up on all the Breaking News Today (Feb. 16, 2026)

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana is Going After Russian Man Who Secretly Films Women During Intimate Encounters

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoThree Killed, Multiple Vehicles Burnt as Fuel Tanker Explodes on Nsawam-Accra Highway

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSilent Turf War Intensifies: U.S. Extends AGOA, China Responds with Zero-Tariff Access to 53 African Nations

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoThe Largest Floating Solar Farm Project in West Africa is in Ghana: Seldomly Talked About But Still Powering Homes

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana Actively Liaising with Burkinabè Authorities After Terrorists Attack Ghanaian Tomato Traders in Burkina Faso

-

Taste GH2 days ago

Taste GH2 days agoOkro Stew: How to Prepare the Ghanaian Stew That Stretches, Survives, and Still Feels Like Home

Natalie Jevons

December 8, 2025 at 6:01 pm

Hello,

Register ghananewsglobal.com in Google Search Index to have it displayed in WebSearch Results.

List ghananewsglobal.com at https://searchregister.net