Africa Watch

Violent Waterfront Demolitions in Lagos Leave Over 10,000 Displaced, At Least 10 Dead

A wave of violent demolitions at a waterfront community in Lagos has displaced more than 10,000 residents over the past month.

According to community leaders and eyewitness accounts, the pace of destruction accelerating sharply in recent days,

Bulldozers and excavators continue to level homes and small businesses in the area known as Aurora Shoki, a sprawling settlement built partly over sandfilled waterfront land. Residents say entire streets have been flattened, leaving families without shelter and livelihoods. On Tuesday morning December 9, 2025, police officers and armed men reportedly set fire to piles of salvaged clothing and personal belongings gathered by displaced residents near demolished structures.

Community representatives say at least 10 people have died during the demolitions, with some reportedly crushed inside their homes as heavy machinery moved in. Many residents told local observers they have no alternative accommodation and are uncertain where they will go next.

Aurora Shoki has long been at the centre of complex land disputes. While the land is officially owned by the Lagos State government, it is also claimed by a traditional ruler, the Oba of Warukii, who has alleged that many residents are occupying the area illegally and engaging in criminal activity.

Residents and landlords reject those claims, insisting they have lived in the community for years and possess legal documents for their properties.

According to residents, attempts to halt the demolitions through legal means have failed. Community members say they presented police with court injunctions obtained with the support of a non-governmental organisation, Justice and Initiative (JI), which barred any evictions without consultation and clear plans for resettlement. They allege the injunctions were ignored as demolitions proceeded.

Most of those affected are low-income workers—cleaners, drivers, artisans and service staff—who support Lagos’ affluent districts but cannot afford formal housing in the city. Community leaders accuse both government authorities and traditional power holders of pushing to clear the waterfront for high-end real estate developments, a trend that has increasingly threatened informal coastal settlements across Lagos.

Lagos, Africa’s most populous city, has faced a prolonged housing crisis for decades. An estimated 70% of its residents live in informal settlements, according to World Bank data. While evictions are not uncommon, rights groups note that even when legally sanctioned, communities typically seek minimal safeguards, including time to relocate people and possessions. In Aurora Shoki, residents say no such allowances were made.

Urban planners and human rights advocates warn that sudden and forceful evictions deepen social vulnerability and perpetuate the very housing crisis that fuels the growth of informal settlements. As demolitions continue, calls are growing for authorities to halt the operation, respect court orders, and urgently address the humanitarian needs of displaced families.

Africa Watch

United States Intensifies Operation in Nigeria as 3 Military Aircraft Deliver Ammunition and More Troops

At least three United States military transport aircraft landed at the Bornu Military Airbase (Maiduguri) and other northeastern bases between Thursday and Friday, February 12–13, 2026.

Reports by Nigerian newspaper Punch, the aircraft delivered ammunition, logistics support, and the vanguard of a planned deployment of American personnel, citing multiple defence sources.

The arrivals were first noted by The New York Times, which reported that C-17 Globemaster III cargo planes landed in Maiduguri on Thursday night, with three aircraft visible by Friday evening as equipment was offloaded. Additional flights were expected over the weekend and in the coming weeks.

A US Department of Defense official described the initial landings as “the vanguard of what will be a stream of C-17 transport flights into three main locations across Nigeria.”

Senior Nigerian Defence Headquarters officers, speaking anonymously to Sunday Punch, confirmed the aircraft carried ammunition supplied by the US government as part of ongoing bilateral security cooperation.

“Following Nigeria-US bilateral talks on security, the American government will not only deploy soldiers but also provide necessary logistics, including ammunition, to fight the insurgents.”

Another high-ranking source explained that the deliveries were routine replenishment of ammunition stocks after operations, noting that Nigeria’s military frequently requires resupply of various calibres.

The officers described the support as coordinated under the National Security Adviser and part of a broader partnership to end insecurity.

A separate X post by counter-terrorism tracker @mobilisingniger reported that a US Air Force C-130J-30 cargo aircraft landed at Kaduna International Airport on Friday after departing from Ghana, fuelling speculation that Kaduna could serve as a training hub for US personnel working with the Nigerian military.

The deployment aligns with President Donald Trump’s 2025 declaration that he would send US forces to Nigeria if the government failed to address what he called “genocide against Christians,” followed by Nigeria’s designation as a Country of Particular Concern. The US carried out an airstrike on Islamic State fighters in Sokoto State on Christmas Day 2025, and bilateral engagements have since deepened.

Experts offered mixed but largely pragmatic assessments. Retired Nigerian Army Intelligence officer Chris Andrew clarified that the arrivals involve technical trainers, drone specialists, and intelligence advisers — not combat troops. He noted recent improvements in Nigerian air operations following US training and suggested Nigeria should seize the opportunity to host a drone base (potentially in Sambisa Forest) after the US withdrawal from Niger.

When U.S. launched strikes against terrorists in Sokoto in December 2025, Security analyst and international intelligence expert Kasambata Yaro cautioned that even a legally sanctioned military operation can generate unease across the region.

“Although Nigeria’s explicit consent addresses the fundamental legal question of sovereignty,” Yaro told Ghana News Global, “the broader regional implications remain complex.”

Nigerian security analyst Chidi Omeje has also told Punch that any cooperation must preserve Nigerian sovereignty, with no foreign troops conducting operations without approval.

The US deployment is expected to focus on targeted counter-terrorism support, drone operations, precision air capabilities, and training to protect vulnerable communities, particularly Christians in the northeast.

No official joint statement has been issued by the Nigerian Defence Headquarters or the US Embassy as of February 16, 2026, but the arrivals signal a significant deepening of US–Nigeria security cooperation amid persistent Boko Haram and ISWAP threats.

Africa Watch

Ghana Elected First Vice-Chair of African Union for 2026 as Burundi Assumes Chairmanship

Ghana has been elected First Vice-Chair of the African Union (AU) for 2026 during the 46th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on February 14, 2026.

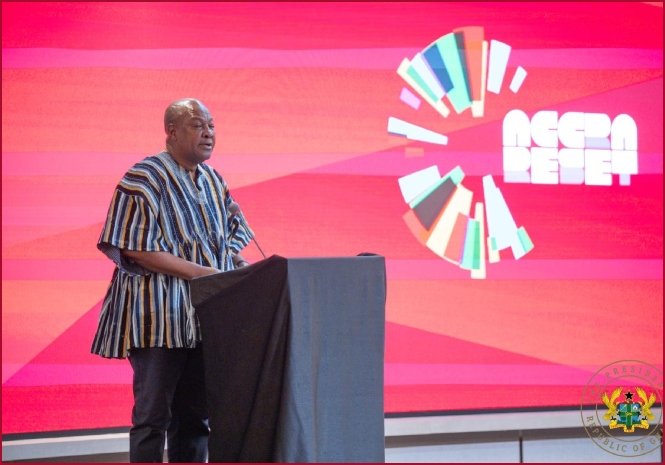

President John Dramani Mahama’s nomination was unanimously endorsed by AU member states, placing Ghana in the second-highest leadership position of the continental body for the coming year.

Burundi’s President Évariste Ndayishimiye officially assumed the AU Chairmanship, succeeding Angola’s João Lourenço, while the full Bureau now reflects balanced regional representation across Africa’s five geographic zones.

The election underscores Ghana’s growing diplomatic influence and its active role in advancing the AU’s core priorities: deepening continental integration, accelerating the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), strengthening peace and security mechanisms, mobilising climate finance, and advancing institutional reforms.

During the summit, President Mahama delivered remarks reinforcing Ghana’s commitment to these goals, including renewed calls for regional manufacturing hubs, vaccine production capacity, and a UN resolution on reparatory justice for the transatlantic slave trade. Ghana’s First Vice-Chair position will give the country a prominent platform to champion these issues over the next 12 months.

The 46th AU Summit, held February 13–18, 2026, adopted the 2026 theme “Assuring Sustainable Water Availability and Safe Sanitation Systems to Achieve the Goals of Agenda 2063,” with leaders also addressing ongoing conflicts, debt burdens, and global economic pressures affecting Africa.

Ghana’s elevation to First Vice-Chair is widely seen as recognition of its consistent advocacy for Pan-African unity, democratic governance, and economic transformation — principles central to the “Reset Ghana” agenda.

Africa Watch

Ghana Continues Push for UN Resolution on Transatlantic Slave Trade Reparations at AU Summit

Ghana has formally urged the African Union (AU) to rally continental support for a proposed United Nations resolution seeking international acknowledgment, accountability, and reparatory justice for the transatlantic slave trade and its enduring legacies.

The call was made during the 46th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa on February 13, 2026.

Ghana’s delegation, led by President John Dramani Mahama, stated that the resolution — currently under discussion at the UN — aims to establish a global framework for formal apology, acknowledgment of historical harm, educational reforms, economic reparations, and debt cancellation for affected nations.

Ghana argued that the slave trade, which forcibly removed an estimated 12–15 million Africans between the 15th and 19th centuries, created lasting structural inequalities, underdevelopment, and racial injustice that persist today. The country positioned the resolution as a moral, legal, and economic imperative for global healing and development justice.

Key elements Ghana is advocating for in the UN text include:

- Official recognition of the transatlantic slave trade as a crime against humanity

- Establishment of an international reparations mechanism

- Support for education curricula reforms worldwide to teach the full history and impact of the trade

- Debt relief and development financing for African nations as partial reparatory measures

- Preservation and digitisation of slave trade archives and memorials

The proposal builds on Ghana’s long-standing leadership on reparations, including the 2019 Year of Return, the establishment of the Emancipation Day holiday, and hosting of multiple Pan-African reparations conferences. It also aligns with the AU’s 2025 Theme of the Year: “Justice for Africans and People of African Descent Through Reparations.”

Ghana’s delegation called on fellow AU member states to co-sponsor the resolution, lobby permanent members of the UN Security Council, and mobilise support in the General Assembly. Several leaders expressed solidarity during closed-door discussions, with follow-up coordination expected through the AU’s Committee of Fifteen on Reparations.

The move reflects Ghana’s continued role as a voice for historical justice and Pan-African solidarity on the global stage.

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoGhana News Live Updates: Catch up on all the Breaking News Today (Feb. 15, 2026)

-

Ghana News17 hours ago

Ghana News17 hours agoGhana News Live Updates: Catch up on all the Breaking News Today (Feb. 16, 2026)

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoGhana is Going After Russian Man Who Secretly Films Women During Intimate Encounters

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSilent Turf War Intensifies: U.S. Extends AGOA, China Responds with Zero-Tariff Access to 53 African Nations

-

Taste GH2 days ago

Taste GH2 days agoOkro Stew: How to Prepare the Ghanaian Stew That Stretches, Survives, and Still Feels Like Home

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoThe Largest Floating Solar Farm Project in West Africa is in Ghana: Seldomly Talked About But Still Powering Homes

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana Actively Liaising with Burkinabè Authorities After Terrorists Attack Ghanaian Tomato Traders in Burkina Faso

-

Ghana News17 hours ago

Ghana News17 hours agoSeveral Ghanaian Traders Feared Dead in the Brutal Terrorist Attack in Burkina Faso