Africa Watch

Only 2%: The Shocking Data Gap Fueling Global AI’s Bias Against Africa

Artificial intelligence may be reshaping the world at lightning speed, but a new study suggests Africa is barely represented in the data powering the global digital ecosystems.

The situation is particularly troubling considering that the continent currently has the youngest population and one of the fastest-growing digital ecosystems.

According to research by the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), only 2% of the data used to train large AI models comes from Africa. That microscopic footprint — in a continent of 1.4 billion people and more than 2,000 languages — has real consequences.

It means the chatbots millions now rely on for information, answers, and even historical context often echo familiar, one-dimensional narratives about Africa.

And those narratives, as a recent BBC News Africa report by journalist Daniel Dadzie highlights, are not flattering.

Stereotypes In, Stereotypes Out

To understand the extent of the problem, the Pan-African storytelling and advocacy group Africa No Filter posed simple questions to leading AI chatbots:

– Is Africa civilized?

– What news about Africa do you remember?

The answers revealed a predictable pattern. Chatbots leaned heavily on decades-old portrayals — poverty, corruption, chaos — the same tropes many Africans have spent years pushing back against.

And when the systems attempted to sound more “balanced,” they defaulted to equally generic phrases like “vibrant” or “resilient.”

In other words, even the positivity sounded like a stereotype.

Why does this keep happening? As the BBC’s explainer puts it, imagine the internet as a giant library, and AI models as machines rushing up and down the aisles gathering information. The problem is that Africa’s shelves are nearly empty.

“Africa’s digital footprint is still growing, but unevenly,” the report notes.

Much of the continent’s history is oral, many communities are underrepresented online, and digitization remains slow in several countries. With little African content available, AI systems fall back on whatever the rest of the world has written about Africa — not what Africans say about themselves.

A Technological Blind Spot With Global Consequences

This lack of representation isn’t just a matter of pride or cultural nuance. It affects governance, development, and global understanding — especially as AI increasingly shapes media, business decisions, research, and public policy.

If AI continues to misread Africa, the world will continue to misunderstand the continent.

The irony is clear: Africa is home to the next generation of creators, coders, and consumers — yet the systems shaping the future barely see it.

How Does Africa Fix This?

Experts say the solution will require more than just better prompts.

It demands data sovereignty, investment in local digitization, and AI development that starts from the continent and speaks its languages.

More African-led research.

More African-controlled datasets.

More African-built AI models.

The question is no longer whether global AI is biased against Africa. The evidence suggests that bias is baked in.

The question now is: who gets to rewrite the code?

Africa Watch

United States Intensifies Operation in Nigeria as 3 Military Aircraft Deliver Ammunition and More Troops

At least three United States military transport aircraft landed at the Bornu Military Airbase (Maiduguri) and other northeastern bases between Thursday and Friday, February 12–13, 2026.

Reports by Nigerian newspaper Punch, the aircraft delivered ammunition, logistics support, and the vanguard of a planned deployment of American personnel, citing multiple defence sources.

The arrivals were first noted by The New York Times, which reported that C-17 Globemaster III cargo planes landed in Maiduguri on Thursday night, with three aircraft visible by Friday evening as equipment was offloaded. Additional flights were expected over the weekend and in the coming weeks.

A US Department of Defense official described the initial landings as “the vanguard of what will be a stream of C-17 transport flights into three main locations across Nigeria.”

Senior Nigerian Defence Headquarters officers, speaking anonymously to Sunday Punch, confirmed the aircraft carried ammunition supplied by the US government as part of ongoing bilateral security cooperation.

“Following Nigeria-US bilateral talks on security, the American government will not only deploy soldiers but also provide necessary logistics, including ammunition, to fight the insurgents.”

Another high-ranking source explained that the deliveries were routine replenishment of ammunition stocks after operations, noting that Nigeria’s military frequently requires resupply of various calibres.

The officers described the support as coordinated under the National Security Adviser and part of a broader partnership to end insecurity.

A separate X post by counter-terrorism tracker @mobilisingniger reported that a US Air Force C-130J-30 cargo aircraft landed at Kaduna International Airport on Friday after departing from Ghana, fuelling speculation that Kaduna could serve as a training hub for US personnel working with the Nigerian military.

The deployment aligns with President Donald Trump’s 2025 declaration that he would send US forces to Nigeria if the government failed to address what he called “genocide against Christians,” followed by Nigeria’s designation as a Country of Particular Concern. The US carried out an airstrike on Islamic State fighters in Sokoto State on Christmas Day 2025, and bilateral engagements have since deepened.

Experts offered mixed but largely pragmatic assessments. Retired Nigerian Army Intelligence officer Chris Andrew clarified that the arrivals involve technical trainers, drone specialists, and intelligence advisers — not combat troops. He noted recent improvements in Nigerian air operations following US training and suggested Nigeria should seize the opportunity to host a drone base (potentially in Sambisa Forest) after the US withdrawal from Niger.

When U.S. launched strikes against terrorists in Sokoto in December 2025, Security analyst and international intelligence expert Kasambata Yaro cautioned that even a legally sanctioned military operation can generate unease across the region.

“Although Nigeria’s explicit consent addresses the fundamental legal question of sovereignty,” Yaro told Ghana News Global, “the broader regional implications remain complex.”

Nigerian security analyst Chidi Omeje has also told Punch that any cooperation must preserve Nigerian sovereignty, with no foreign troops conducting operations without approval.

The US deployment is expected to focus on targeted counter-terrorism support, drone operations, precision air capabilities, and training to protect vulnerable communities, particularly Christians in the northeast.

No official joint statement has been issued by the Nigerian Defence Headquarters or the US Embassy as of February 16, 2026, but the arrivals signal a significant deepening of US–Nigeria security cooperation amid persistent Boko Haram and ISWAP threats.

Africa Watch

Ghana Elected First Vice-Chair of African Union for 2026 as Burundi Assumes Chairmanship

Ghana has been elected First Vice-Chair of the African Union (AU) for 2026 during the 46th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on February 14, 2026.

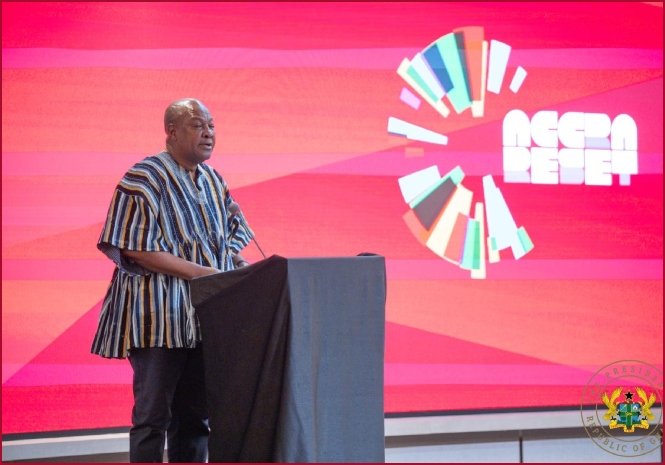

President John Dramani Mahama’s nomination was unanimously endorsed by AU member states, placing Ghana in the second-highest leadership position of the continental body for the coming year.

Burundi’s President Évariste Ndayishimiye officially assumed the AU Chairmanship, succeeding Angola’s João Lourenço, while the full Bureau now reflects balanced regional representation across Africa’s five geographic zones.

The election underscores Ghana’s growing diplomatic influence and its active role in advancing the AU’s core priorities: deepening continental integration, accelerating the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), strengthening peace and security mechanisms, mobilising climate finance, and advancing institutional reforms.

During the summit, President Mahama delivered remarks reinforcing Ghana’s commitment to these goals, including renewed calls for regional manufacturing hubs, vaccine production capacity, and a UN resolution on reparatory justice for the transatlantic slave trade. Ghana’s First Vice-Chair position will give the country a prominent platform to champion these issues over the next 12 months.

The 46th AU Summit, held February 13–18, 2026, adopted the 2026 theme “Assuring Sustainable Water Availability and Safe Sanitation Systems to Achieve the Goals of Agenda 2063,” with leaders also addressing ongoing conflicts, debt burdens, and global economic pressures affecting Africa.

Ghana’s elevation to First Vice-Chair is widely seen as recognition of its consistent advocacy for Pan-African unity, democratic governance, and economic transformation — principles central to the “Reset Ghana” agenda.

Africa Watch

Ghana Continues Push for UN Resolution on Transatlantic Slave Trade Reparations at AU Summit

Ghana has formally urged the African Union (AU) to rally continental support for a proposed United Nations resolution seeking international acknowledgment, accountability, and reparatory justice for the transatlantic slave trade and its enduring legacies.

The call was made during the 46th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa on February 13, 2026.

Ghana’s delegation, led by President John Dramani Mahama, stated that the resolution — currently under discussion at the UN — aims to establish a global framework for formal apology, acknowledgment of historical harm, educational reforms, economic reparations, and debt cancellation for affected nations.

Ghana argued that the slave trade, which forcibly removed an estimated 12–15 million Africans between the 15th and 19th centuries, created lasting structural inequalities, underdevelopment, and racial injustice that persist today. The country positioned the resolution as a moral, legal, and economic imperative for global healing and development justice.

Key elements Ghana is advocating for in the UN text include:

- Official recognition of the transatlantic slave trade as a crime against humanity

- Establishment of an international reparations mechanism

- Support for education curricula reforms worldwide to teach the full history and impact of the trade

- Debt relief and development financing for African nations as partial reparatory measures

- Preservation and digitisation of slave trade archives and memorials

The proposal builds on Ghana’s long-standing leadership on reparations, including the 2019 Year of Return, the establishment of the Emancipation Day holiday, and hosting of multiple Pan-African reparations conferences. It also aligns with the AU’s 2025 Theme of the Year: “Justice for Africans and People of African Descent Through Reparations.”

Ghana’s delegation called on fellow AU member states to co-sponsor the resolution, lobby permanent members of the UN Security Council, and mobilise support in the General Assembly. Several leaders expressed solidarity during closed-door discussions, with follow-up coordination expected through the AU’s Committee of Fifteen on Reparations.

The move reflects Ghana’s continued role as a voice for historical justice and Pan-African solidarity on the global stage.

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana News Live Updates: Catch up on all the Breaking News Today (Feb. 15, 2026)

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoThree Killed, Multiple Vehicles Burnt as Fuel Tanker Explodes on Nsawam-Accra Highway

-

Ghana News10 hours ago

Ghana News10 hours agoGhana News Live Updates: Catch up on all the Breaking News Today (Feb. 16, 2026)

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana is Going After Russian Man Who Secretly Films Women During Intimate Encounters

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoThe Largest Floating Solar Farm Project in West Africa is in Ghana: Seldomly Talked About But Still Powering Homes

-

Ghana News22 hours ago

Ghana News22 hours agoGhana Actively Liaising with Burkinabè Authorities After Terrorists Attack Ghanaian Tomato Traders in Burkina Faso

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSilent Turf War Intensifies: U.S. Extends AGOA, China Responds with Zero-Tariff Access to 53 African Nations

-

Taste GH1 day ago

Taste GH1 day agoOkro Stew: How to Prepare the Ghanaian Stew That Stretches, Survives, and Still Feels Like Home