Commentary

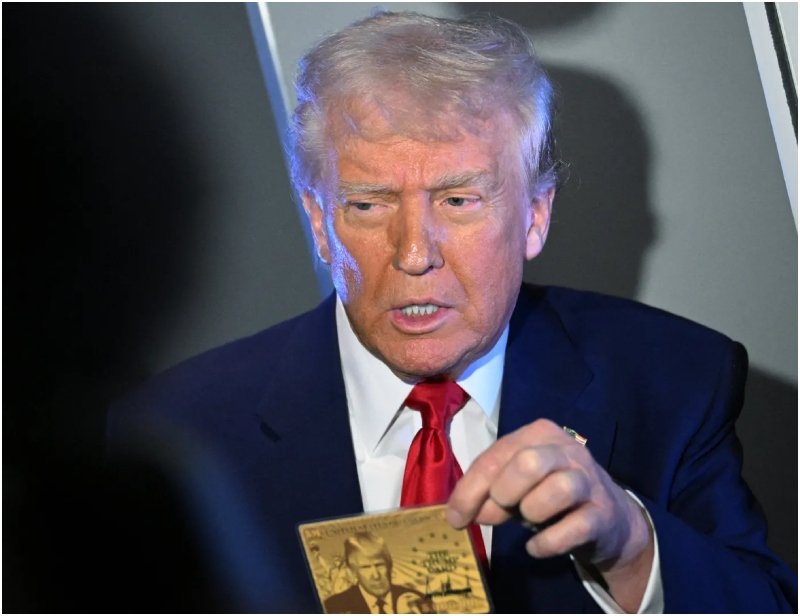

Donald Trump’s first step to becoming a would-be autocrat – hijacking a party

By Justin Bergman, The Conversation

We used to have a pretty clear idea of what an autocrat was. History is full of examples: Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, along with Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping today. The list goes on.

So, where does Donald Trump fit in?

In this six-part podcast series, The Making of an Autocrat, we are asking six experts on authoritarianism and US politics to explain how exactly an autocrat is made – and whether Trump is on his way to becoming one.

Like strongmen around the world, Trump’s first step was to take control of a party, explains Erica Frantz, associate professor of political science at Michigan State University.

Trump began this process long before his victory in the 2024 US presidential election. When he first entered the political stage in 2015, he started to transform the Republican Party into his party, alienating his critics, elevating his loyalists to positions of power and maintaining total control through threats and intimidation.

And once a would-be autocrat dominates a party like this, they have a legitimate vehicle to begin dismantling a democracy. As Frantz explains:

Now, many Republican elites see it as political suicide to stand up to Trump. So, fast forward to 2024, and we have a very personalist Trump party – the party is synonymous with Trump.

Not only does the party have a majority in the legislature, but it is Trump’s vehicle. And our research has shown this is a major red flag for democracy. It’s going to enable Trump to get rid of executive constraints in a variety of domains, which he has, and pursue his strongman agenda.

Listen to the interview with Erica Frantz at The Making of an Autocrat podcast.

This episode was written by Justin Bergman and produced and edited by Isabella Podwinski and Ashlynne McGhee. Sound design by Michelle Macklem.

Newsclips in this episode from CNN, The Telegraph, CNN and Nayib Bukele’s YouTube channel.

Listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feedor find out how else to listen here. A transcript of this episode is available via the Apple Podcasts or Spotify apps.

Justin Bergman, International Affairs Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Commentary

At a glance: US‑Israel attack on Iran

Digital Storytelling Team, The Conversation

The US and Israel have launched joint coordinated attacks on Iran, prompting retaliatory strikes from Iran on Israel and US military bases in the region.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader for 36 years, has been killed in the strikes, Iranian state media reported.

Iran’s Supreme National Security Council says he was killed early Saturday morning at his office. Satellite imagery shows significant damage to parts of the Leadership House compound, which is Khamenei’s office in Tehran.

Iranian school struck

More than 100 children have reportedly been killed by US and Israeli air strikes on a school, according to Iranian authorities. They say the strikes hit a girls’ elementary school in the city of Minab in the country’s south.

Video has emerged of crowds of people searching through the rubble.

“Hundreds of civilians have been killed and injured as a result of the aggression and atrocious crime of the United States regime and the Israeli regime, and the deliberate … targeting of civilian infrastructure,” Amir-Saeid Iravani, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, told an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council.

Digital Storytelling Team, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Commentary

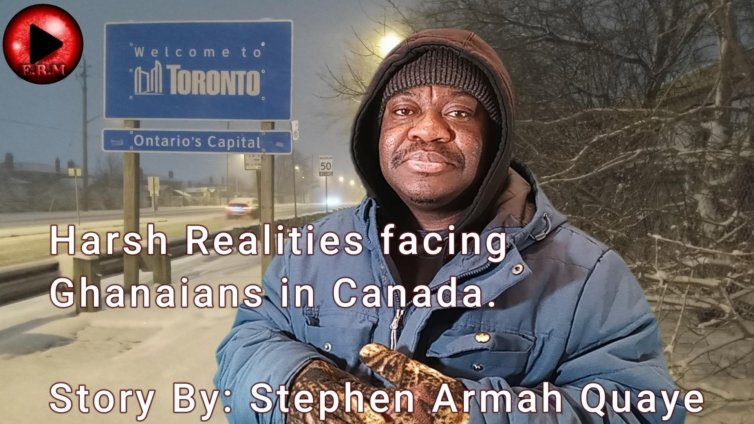

Harsh realities facing Ghanaians in Canada

In this revealing commentary, Stephen Armah Quaye dismantles the popular myth that migration to Canada guarantees automatic success and prosperity for Ghanaians. Drawing attention to the stark contrast between social media portrayals and lived reality, Quaye outlines the multifaceted challenges facing Ghanaian immigrants: brutal winter conditions that test physical and mental endurance, professional downgrading where credentials go unrecognized, a punishing housing crisis that forces overcrowded living arrangements, and the relentless pressure of high living costs that necessitates multiple jobs just for survival. Beyond the economic hardships, he explores the emotional toll of family separation, social isolation, and the often-unspoken burden of expectations from relatives back home who assume wealth is instantaneous upon arrival.

Harsh realities facing Ghanaians in Canada

By Stephen Armah Quaye

Everyone wants to travel to Canada or the United States of America.

Everyone believes life there is easy. But what if I told you that for thousands of Ghanaians abroad, survival, not success, is the daily struggle? There is a side of migration nobody posts on social media. No filters. No airport photos. No smiling selfies in winter jackets. Just hard truths.

Before you pack your bags and say goodbye to Ghana, here is what you need to know.

The Other Side of the Dream

For many young Ghanaians, Canada represents opportunity, stability, and prosperity. It is seen as a land where hard work automatically produces success. Families gather at airports with tears of joy, believing their relative is stepping into an instant transformation. But migration is not magic. It is a transition, often a difficult one.

The Weather Shock

One of the first harsh realities facing Ghanaians in Canada is the weather.

Coming from a tropical country where sunshine dominates most of the year, winter in Canada can be physically and emotionally overwhelming. Temperatures drop far below zero. Snow blankets roads and sidewalks. The wind can pierce through layers of clothing. Winter is not just cold; it is exhausting.

Many immigrants wake up as early as 4:00 a.m., stepping into darkness and freezing temperatures to catch buses to work. Public transport delays during snowstorms are common. Walking even short distances becomes physically demanding.

Seasonal depression is real. Long months without adequate sunlight affect mood, energy, and mental health. For someone unprepared, winter alone can become a serious emotional test.

Employment and Credential Barriers

Another harsh reality is employment, specifically underemployment.

Many Ghanaians arrive with degrees and professional experience. Engineers, teachers, accountants, nurses, and other skilled workers often discover that their credentials are not immediately recognised in Canada. Licensing requirements, additional certifications, and “Canadian experience” become barriers.

As a result, many find themselves taking survival jobs such as factory work, warehouse labour, cleaning services, security shifts, or restaurant jobs. There is dignity in all honest work, but it can be emotionally draining when years of education do not translate into professional recognition. Some immigrants send money home and project success, but internally they struggle with frustration and identity loss. The reality is simple: being educated does not guarantee immediate success in Canada.

The Housing Crisis

Housing is another significant challenge. Rent in major Canadian cities is extremely expensive. In some cases, a single room can consume more than half of a person’s monthly income. Apartments require credit checks, proof of employment, and deposits. As a result, many newcomers share accommodation. Two or three people may occupy one bedroom. Some live-in basements with limited ventilation. Others rely on temporary stays with friends until they stabilise financially.

Meanwhile, families back home may assume their relative abroad owns a spacious apartment or house. The truth is different. Many immigrants are simply trying to secure safe and affordable shelter.

High Cost of Living

The cost of living in Canada is significantly higher than many expect.

Groceries are expensive. Transportation costs add up quickly. Winter clothing is costly but necessary. Phone bills, internet services, and insurance payments are ongoing financial commitments.

Healthcare in Canada is publicly funded, but not everything is covered. Dental care, prescription medication, and some specialist services often require private insurance or out-of-pocket payment.

For many immigrants, income disappears quickly once bills are paid. Savings take time. Financial stability does not happen overnight. This financial pressure pushes some individuals to work two or even three jobs, often with little rest. The goal is not luxury. The goal is survival.

Utility Bills and Winter Expenses

Winter brings additional financial strain.

Heating costs rise significantly during cold months. Electricity and gas bills can increase unexpectedly. Missing payments can lead to service disruptions and penalties.

Life can become a cycle: work, pay bills, repeat. The image of comfort and ease often portrayed abroad does not reflect this ongoing pressure.

Social Isolation and Emotional Strain

Beyond economics, there is emotional hardship. Migration separates families. Parents miss milestones in their children’s lives. Spouses endure long-distance marriages. Friendships change.

Loneliness is common, especially during the early years. Community networks help, but the adjustment period can be mentally challenging. Cultural differences, accent barriers, and subtle discrimination can also make integration difficult.

Pressure from Home

Perhaps one of the most overlooked realities is pressure from back home. Families often expect financial support. Some assume that anyone living in Canada is wealthy. When money does not flow as expected, disappointment may arise.

In some cases, funds sent home for projects such as building houses are mismanaged. This adds emotional and financial stress to an already difficult situation. Expectations can weigh heavily on immigrants who are still struggling to establish themselves.

A Call for Informed Migration

This article is not meant to discourage migration. Canada offers opportunities, safety, quality education, and structured systems. Many Ghanaians have succeeded and built fulfilling lives there.

However, success requires preparation so, if you are considering migration, research your profession and licensing requirements, save sufficient funds before travelling, prepare mentally for weather and cultural adjustment, develop adaptable skills, and build realistic expectations.

Migration is not an escape from hardship; it is often a different kind of hardship. The dream is possible, but it is earned through resilience, patience, sacrifice, and strategic planning.

Before you migrate, know the full story, not just the glamorous parts. Because sometimes, survival itself is an achievement.

Commentary

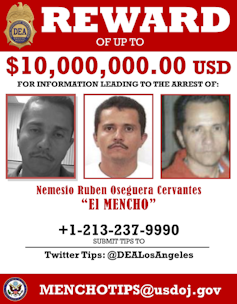

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

The recent death of Jalisco New Generation Cartel leader Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, known as “El Mencho,” has triggered severe retaliatory violence in Mexico, resulting in at least 73 deaths. This article analyzes the event as part of a predictable and counterproductive pattern in Mexico’s security strategy. The author, Angélica Durán-Martínez, an expert on Latin American criminal groups, argues that while high-profile hits like this one serve political purposes by demonstrating action, they rarely dismantle criminal networks. Instead, they often lead to immediate violent backlash and longer-term fragmentation as factions fight for control.

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

By Angélica Durán-Martínez, UMass Lowell

The death of a major cartel boss in Mexico has unleashed a violent backlash in which members of the criminal group have paralyzed some cities through blockades and attacks on property and security forces.

At least 73 people have died as a result of the operation to capture Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, or “El Mencho.” The head of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel was seriously wounded during a firefight with authorities on Feb. 22, 2026. He later died in custody.

As an expert in criminal groups and drug trafficking in Latin America who has been studying Mexico’s cartels for two decades, I see the violent aftermath of the operation as part of a pattern in which Mexican governments have opted for high-profile hits that often lead only to more violence without addressing the broader security problems that plague huge swaths of the country.

Who was ‘El Mencho’?

Like many other figures involved in Mexico’s drug trafficking, Oseguera Cervantes started at the bottom and made his way up the ranks. He spent some time in prison in the U.S., where he may have forged alliances with criminal gangs before being deported back to Mexico in 1997. There, he connected with the Milenio Cartel, an organization that first allied, and then fought with, the powerful Sinaloa Cartel.

Most of the information available points to the Jalisco New Generation Cartel forming under El Mencho around 2010, following the killing of Ignacio “Nacho” Coronel Villarreal, a Sinaloa Cartel leader and main link with the Milenio Cartel.

Since 2015, Jalisco New Generation Cartel has been known for its blatant attacks against security forces in Mexico – such as gunning down a helicopter in that year. And it has expanded its presence both across Mexico and internationally.

In Mexico, it is said to have a presence in all states. In some, the cartel has a direct presence and very strong local networks. In others, it has cultivated alliances with other trafficking organizations.

Besides drug trafficking, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel is also engaged in oil theft, people smuggling and extortion. As a result, it has become one of the most powerful cartels in Mexico.

What impact will his death have on the cartel?

There are a few potential scenarios, and a lot will depend on what succession plans Jalisco New Generation had in the event of Oseguera Cervantes’ capture or killing.

In general, these types of operations – in which security forces take out a cartel leader – lead to more violence, for a variety of reasons.

Mexicans have already experienced the immediate aftermath of Oseguera Cervantes’ death: retaliation attacks, blockades and official attempts to prevent civilians from going out. This is similar to what occurred after the capture of drug lord Ovidio Guzmán López in Sinaloa in 2019 and his second capture in 2023.

Violence flares in two ways following such high-profile captures and killings of cartel leaders.

In the short term, there is retaliation. At the moment, members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel are seeking revenge against Mexico’s security forces and are also trying to assert their regional authority despite El Mencho’s death.

These retaliatory campaigns tend to be violent and flashy. They include blockades as well as attacks against security forces and civilians.

Then there is the longer-term violence associated with any succession. This can take the form of those who are below Oseguera Cervantes in rank fighting for control. But it can also result from rival groups trying to take advantage of any leadership vacuum.

The level and duration of violence depend on a few factors, such as whether there was a succession plan and what kind of alliances are in place with other cartels. But generally, operations in which a cartel boss is removed lead to more violence and fragmentation of criminal groups.

Of course, people like Oseguera Cervantes who have violated laws and engaged in violence need to be captured. But in the long run, that doesn’t do anything to dismantle networks of criminality or reduce the size of their operations.

What is the current state of security in Mexico?

The upsurge in violence after Oseguera Cervantes’ killing occurs as some indicators in Mexico’s security situation seemed to be improving.

For example, homicide rates declined in 2025 – which is an important indicator of security.

But other measures are appalling. Disappearances are still unsettlingly high. The reality that many Mexicans experience on the ground is one where criminal organizations remain powerful and embedded in the local ecosystems that connect state agents, politicians and criminals in complex networks.

Criminal organizations are engaged in what we academics call “criminal governance.” They engage in a wide range of activities and regulate life in communities – sometimes coercively, but sometimes also with some degree of legitimacy from the population.

In some states like Sinaloa, despite the operations to take out cartel’s leaders, the illicit economies are still extensive and profitable. But what’s more important is that levels of violence remain high and the population is still suffering deeply.

The day-to-day reality for people in some of these regions is still one of fear.

And in the greater scheme of things, criminal networks are still very powerful – they are embedded in the country’s economy and politics, and connect to communities in complex ways.

How does the El Mencho operation fit Mexico’s strategy on cartels?

The past two governments vowed to reduce the militarization of security forces. But the power of the military in Mexico has actually expanded.

The government of President Claudia Sheinbaum wanted a big, visible hit at a time when the U.S. is pushing for more militarized policies to counter Mexico’s trafficking organizations.

But this dynamic is not new. Most U.S. and Mexican policy regarding drug trafficking organizations has historically emphasized these high-profile captures – even if it is just for short-term gains.

It’s easier to say “we captured a drug lord” than address broader issues of corruption or impunity. Most of the time when these cartel leaders are captured or killed, there is generally no broader justice. It isn’t accompanied with authorities investigating disappearances, murders, corruption or even necessarily halting the flow of drugs.

Captures and killings of cartel leaders serve a strategic purpose of showing that something is being done, but the effectiveness of such policies in the long run is very limited.

Of course, taking out a drug lord is not a bad thing. But if it does not come with a broader dismantling of criminal networks and an accompanying focus on justice, then the main crimes that these groups commit – homicides, disappearances and extortion – will continue to affect the daily life of people. And the effect on illicit flows is, at best, meager.

Angélica Durán-Martínez, Associate Professor of Political Science, UMass Lowell

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

News13 hours ago

News13 hours agoGhana Gears Up for Vibrant 69th Independence Day Celebrations: Parades, Plays, Poetry, and Heritage in Focus

-

Tourism11 hours ago

Tourism11 hours agoEmirates Resumes Limited Flights from Dubai as Middle East Airspace Slowly Reopens Amid Ongoing Conflict

-

Ghana News14 hours ago

Ghana News14 hours agoNewspaper Headlines Today: Tuesday, March 3, 2026

-

Ghana News14 hours ago

Ghana News14 hours agoAyawaso East By-Election Results Trickle in, ECG Audits Fast-Reading Meters, and Other Trending Topics in Ghana (March 3, 2026)

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoCourt Slaps Barker-Vormawor with GH₵5m for Defaming Kan Dapaah and Other Trending Topics in Ghana (March 2, 2026)

-

Fashion & Style5 hours ago

Fashion & Style5 hours agoThe New Wave of “Afro-Minimalism”: Redefining Luxury Beyond the Print

-

Ghana News4 hours ago

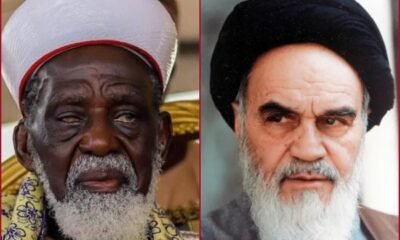

Ghana News4 hours agoGhana’s Top Muslim Leader Condemns Khamenei Assassination, Calls for New World Order Based on ‘Right Over Might’

-

Commentary11 hours ago

Commentary11 hours agoAt a glance: US‑Israel attack on Iran