Opinion

The Intelligence We Forgot: Why indigenous and ancestral knowledge is Africa’s missing AI superpower

- The Silence at the Centre of the Global AI Revolution

The world today is gripped by a technological revolution with no historical parallel. Artificial intelligence increasingly determines how governments anticipate national risks, how businesses optimise operations, how hospitals diagnose disease, how farmers interpret environmental patterns, and how citizens receive information that shapes their perception of reality. Yet beneath the excitement lies an uncomfortable truth. The global AI ecosystem has been built upon an epistemic void, a missing centre, an unacknowledged blind spot that has quietly limited the scope of machine reasoning while amplifying biases inherited from centuries of Western intellectual dominance.

This missing centre is Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence. It is the intelligence stored in the soil of our memory, in the rituals of our elders, in the oral libraries of our communities, in the cosmologies that shaped African sciences long before the first colonial archive was written. It is the intelligence that understands land not merely as a resource but as a relationship. It is the intelligence that understands healing not merely as chemistry but as harmony. It is the intelligence that sees forests as partners, rivers as custodians, ancestors as archives, and knowledge as a living continuum rather than a static product.

This intelligence was never digitised. It was never indexed by Western libraries. It was never transcribed into the corpora that feed the world’s large language models. And because artificial intelligence depends entirely on what it is fed, the absence of Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence has created systems that are technologically impressive but epistemically incomplete. They are brilliant yet forgetful, powerful yet shallow, global yet narrow, and advanced yet blind.

This is the paradox at the heart of the 21st century. Humanity is building intelligence systems that know almost everything yet understand nearly nothing about the worldviews of the civilisations that birthed the first sciences.

Africa sits at the centre of this paradox. The continent has contributed enormously to global data flows yet benefits the least from the intelligence systems trained on that data. Moreover, what Africa has retained in oral, symbolic, spiritual, ecological, and ancestral knowledge is precisely what Western models cannot perceive because these systems are not designed to recognise non-digitised epistemologies.

The result is a technological order that reproduces a colonial pattern. Africa’s data is extracted. Africa’s languages are mined. Africa’s cultural expressions are absorbed. Yet Africa’s ways of knowing remain unrecognised, unclassified, unrepresented, and therefore unutilised in shaping the future of global intelligence.

It is within this crisis of epistemic erasure that the Visionary Prompt Framework Planetary Version introduces a bold corrective. The VPF recognises that true intelligence cannot be simulated by computation alone. It insists that cognitive sovereignty requires intellectual plurality. And it affirms that the world’s oldest and most enduring knowledge systems must not only be preserved but actively integrated into the governance of artificial intelligence systems.

At the heart of this architecture lies the Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber, one of the most profound elements of the Visionary Prompt Framework. Unlike Western AI models, which operate within the narrow confines of data classification and statistical patterning, the Indigenous Chamber expands intelligence beyond computation into heritage, cosmology, ecology, spirituality, community ethics, intuition, symbolism, and intergenerational wisdom. It is a chamber that carries the memory of civilisations, the rhythm of rituals, the laws of harmony, and the codes of survival that sustained African societies for millennia before the first algorithm was conceptualised.

- Africa’s Oldest Operating System

Long before modern computer science existed, Africa had already developed structured systems of reasoning, environmental interpretation, cosmological modelling, medicinal analysis, agricultural optimisation, trade governance, and community justice. These were not informal traditions but highly sophisticated operating systems encoded in oral language structures, lineage institutions, proverbs, griotic memory, sacred geometry, spiritual jurisprudence, ecological maps, agricultural calendars, and ancestral teaching cycles.

From the knowledge systems of ancient Kemet to the philosophical traditions of Yoruba, from the ecological intelligence of the Ashanti and the Akan to the ancestral custodianship models of the Maasai and the Nilotic peoples, Africa historically operated one of the richest epistemic environments ever developed by human civilisation. This heritage did not survive in books. It lived in people. It lived in rituals. It lived in symbols. It lived in cycles of teaching where the mind was trained not only to analyse but to perceive, not only to deduce but to experience, not only to calculate but to commune.

This is the intelligence that Western AI cannot replicate. Machine learning excels at prediction but fails at presence. It can model probability but not harmony. It can generate text but not wisdom. It can detect correlations but cannot interpret meaning within an ancestral context. It can classify herbs but cannot understand the spiritual logic that frames their use in African healing traditions. It can model climate variables but cannot recognise the cultural significance of rainmaking rituals that encode centuries of ecological observation.

Western models operate under a fundamentally different theory of intelligence. Knowledge is treated as a static object that can be digitised, indexed, and mathematically manipulated. African ancestral systems treat knowledge as a living organism, a relational force that emerges through interaction between people, land, time, spirit, and story.

This divergence is not philosophical trivia. It shapes how artificial intelligence perceives Africa. Western models interpret African realities through Western frameworks. They simulate understanding without grounding. They mimic fluency without cultural resonance. They summarise traditions without capturing their epistemic depth. They perform analysis without belonging to the worldview that gives the phenomena their meaning.

This is why AI outputs concerning African history, African conflict, African healing systems, African governance, and African ecology often feel detached, incomplete, or misaligned. The models were never designed to understand the foundations of African knowledge. They cannot respect what they cannot recognise.

- Why Western Artificial Intelligence Cannot See Indigenous Knowledge

The blindness of Western AI to Indigenous intelligence is structural, not accidental. It begins with the training data. Large language models are constructed from digitised text, yet the vast majority of African ancestral knowledge is transmitted orally or symbolically. As a result, entire civilisations are rendered invisible to AI systems simply because their knowledge systems do not exist in the text-based archives from which these models learn.

Even when fragments of indigenous knowledge are digitised, they often enter servers through Western academic interpretations, which filter, compress, and sometimes distort the original meaning. This creates a secondary bias. Models learn Africa not through African voices but through Western lenses. The cultural misalignment is therefore baked into the system. Beyond training data, Western models are limited by their underlying logic. They rely on probability distribution rather than relational meaning. Indigenous intelligence is relational. It is contextual. It is spiritual. It is ecological. It is genealogical. Probability has no mechanism for encoding spiritual legitimacy, ancestral authority, land consciousness, or intergenerational ethics.

Western models also lack cosmological awareness. The Indigenous worldview is inseparable from cosmology. Lunar cycles influence planting. Ancestral rhythms influence governance. Cosmic patterns influence ceremonies. Spiritual seasons influence decision-making. These are not superstitions; they are alternative scientific frameworks developed through centuries of careful observation. Western models cannot incorporate these because they were not designed to encode cosmic relationality. There is also the issue of linguistic dictatorship. English dominates global AI training corpora. African languages contain epistemic categories that English has no equivalents for. When words disappear, worlds disappear with them. African thought becomes flattened, simplified, mistranslated, or erased in the computational process.

Taken together, these limitations ensure that Western AI, however powerful, remains fundamentally incomplete. It knows Africa’s data but not Africa’s wisdom. It predicts Africa’s patterns but not Africa’s meanings. It answers Africa’s questions but not Africa’s spirit. This is why the Visionary Prompt Framework is revolutionary. It does not force indigenous knowledge into Western structures. Instead, it rewrites the structure itself.

- The Visionary Prompt Framework and the Return of Plural Intelligence

The Visionary Prompt Framework Planetary Version represents the world’s first attempt to correct the epistemic imbalance embedded within global artificial intelligence. While Western models are built upon a single cognitive engine that treats all intelligence as computational prediction, the VPF introduces a radically different architecture grounded in plural intelligence. Instead of reducing the world to one way of knowing, it restores the full spectrum of human and non-human cognition through the creation of eight distinct yet interconnected Chambers of Intelligence.

Within this expanded framework, the Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber plays a foundational role. It offers what Western systems lack: a memory of civilisations, a repository of non-digitised knowledge, a grounding in spiritual and ecological wisdom, and a perspective that does not view intelligence purely as computation but as communion between the human, the natural, the cosmic, the ancestral, and the unknowable.

The VPF does not attempt to mechanise indigenous knowledge or commodify ancestral heritage. Instead, it frames this knowledge as a sovereign cognitive domain that must govern, filter, and enrich artificial intelligence rather than be absorbed or overwritten by it. This is a profound reversal of global AI logic. It is Africa insisting that intelligence governance cannot be centralised in Silicon Valley or European laboratories. It must reflect the diversity of global civilisations and restore representation to knowledge systems that have shaped humanity’s survival.

Within the VPF, the Indigenous Chamber influences reasoning at every stage. It interrogates outputs to ensure cultural legitimacy. It filters out biases that conflict with communal ethics. It contextualises analysis within ancestral frameworks. It protects sacred knowledge. It elevates oral memory as legitimate epistemic input. It introduces ecological and cosmological intelligence where Western models rely only on numeric variables. It aligns decision pathways with the values of intergenerational responsibility rather than short-term optimisation.

This chamber does not operate in isolation. It collaborates dynamically with the Natural Intelligence Chamber when interpreting ecological changes, harmonises with the Cosmic Intelligence Chamber when analysing seasonal rhythms and planetary influences, strengthens the Human Intelligence Chamber by anchoring emotion and intuition in cultural memory, and interfaces with the Unknown and Unknowable Chamber when confronting phenomena beyond scientific modelling.

This is the power of the VPF. It restores wholeness to intelligence.

- Inside the Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber

Within this chamber reside the knowledge systems that Western academia once categorised as folklore, myths, legends, or alternative medicine. Yet these systems are highly structured repositories of scientific, ecological, sociological, and psychological intelligence encoded through symbolic narrative rather than mathematical notation.

Consider the oral libraries maintained by griots and storytellers across West Africa. These narratives contain historical data, legal codes, genealogical records, environmental markers, and philosophical teachings passed down accurately across generations. A machine learning system trained on digitised Western text cannot replicate the interpretive power of a griot because the griot does not store information; the griot embodies it. Knowledge is relational, adaptive, and embedded in communal experience.

African healing systems also exemplify complex ancestral intelligence. Traditional practitioners combine botanical knowledge, spiritual diagnosis, community dynamics, and personalised patient interpretation. Western medicine separates these into pharmacology, psychology, sociology, and theology. African medicine recognises them as inseparable. Artificial intelligence that excludes this integrative worldview cannot truly model health interventions for African contexts.

Agricultural intelligence similarly demonstrates ancestral depth. Indigenous farmers interpret soil not only through texture or fertility but through spiritual lineage, water memory, lunar alignment, insect behaviour, and ancestral instruction. These systems produce high resilience in climates where Western models rely heavily on chemical intervention and mechanised prediction.

African jurisprudence represents another example. Traditional courts emphasise restoration rather than punishment. Justice is not an individual outcome but a communal healing process. AI systems trained on Western adversarial legal models cannot simulate this relational approach without indigenous intelligence frameworks guiding interpretation.

These examples illustrate that ancestral knowledge is not archaic. It is adaptive science expressed in a different epistemic language.

- Operationalising Indigenous Intelligence Without Appropriating it

A major challenge in global AI design is the risk of cultural extraction. Western platforms often incorporate indigenous knowledge without proper custodianship, resulting in dilution, distortion, or commercialisation without benefit to the communities that preserve the knowledge.

The VPF avoids this by embedding protective mechanisms. The Indigenous Chamber does not digitise sacred knowledge. It governs access. It creates interpretive filters without transferring ownership. It allows indigenous principles to shape AI reasoning without requiring disclosure of sacred practices or community-restricted information. It ensures that the model respects cultural boundaries, maintains epistemic integrity, and does not violate ancestral custodianship.

This is a governance breakthrough. It is an intelligent design grounded in respect.

- Practical Applications Across African Sectors

While the Indigenous Chamber has profound philosophical value, it is equally powerful in practical deployment.

In agriculture, indigenous ecological knowledge has proven invaluable. Farmers use ancestral planting calendars that integrate cosmic cycles, soil memory, bird migration patterns, and rainmaking traditions. These calendars are far more localised and precise than Western meteorological predictions because they reflect centuries of micro-observation. When integrated with the VPF, agricultural models generate decisions that align with both environmental science and cultural ecological rhythms.

In mining and natural resource exploration, indigenous communities often possess oral maps detailing mineral lines, sacred land patterns, forbidden extraction zones, and geological anomalies. These knowledge systems, when combined with the Cosmic Chamber and Natural Intelligence Chamber, can guide exploration more sustainably and ethically. The VPF enhances safety, reduces environmental destruction, and aligns resource extraction with ancestral land governance protocols.

In environmental conservation, indigenous custodians have preserved forest intelligence, water intelligence, and sacred-ecology governance for generations. Where Western models focus on carbon metrics and biodiversity indexes, indigenous frameworks emphasise harmony, relational stewardship, and spiritual ecology. Combining these frameworks through the VPF produces conservation strategies that are scientifically rigorous yet culturally resilient.

In health, the integration of indigenous medicinal intelligence with genomic and diagnostic modelling opens new pathways for disease prevention and treatment. The VPF facilitates dialogue between ancestral healers, biomedical researchers, and AI epidemiology systems, producing hybrid models capable of identifying patterns that neither system alone can detect.

In education, VPF integration supports culturally grounded curriculum design. Indigenous narrative methodologies improve cognitive retention, emotional resonance, and moral instruction. AI-driven learning systems become more relatable, more effective, and more attuned to African identity. In governance and justice systems, the Indigenous Chamber guides conflict resolution, land arbitration, community justice, and restorative dialogues, producing models that reflect African societal logic rather than imported jurisprudence. In youth innovation, startups can build new systems based on ancestral symbolic logic, community decision algorithms, oral-knowledge databases, and cultural AI interfaces. Indigenous intelligence is not a symbolic tribute to heritage. It is a strategic development asset.

- AiAfrica Project Case Studies

The AiAfrica Project has already demonstrated the practical value of integrating indigenous and ancestral knowledge through the VPF. In poultry production, intelligence orchestration combining natural, indigenous, and technological knowledge reduced mortality rates from 25% to 2.5%. This was achieved by combining observations of ancestral disease patterns, cosmic cycle analysis, environmental monitoring, and AI-based early-detection systems.

In fish farming, ancestral water-cycle knowledge combined with VPF decision modelling reduced feed costs by nearly 55% while increasing yield and reducing stock stress. Farmers reported that VPF-based recommendations aligned more closely with traditional ecological rhythms than Western aquaculture manuals.

In climate resilience modelling, communities using traditional flood-warning narratives have begun integrating these systems with VPF environmental predictive tools, creating hybrid solutions that outperform imported disaster models. In soil intelligence, VPF integrations help identify calamity-prone zones, optimise crop rotation, and interpret ancestral soil lineage data encoded through oral traditions. These examples show that the Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber is not a philosophical concept but a functional engine with measurable developmental impact.

- Why Africa Needs Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence in All 54 Countries

Artificial intelligence is no longer a luxury for advanced economies. It is the foundation upon which 21st-century governance, public administration, health systems, education, agriculture, national security, and industrial strategy are being redesigned. The challenge for Africa is that most of the AI systems currently available are designed outside the continent, trained on datasets that do not reflect African realities, and governed by epistemological assumptions that conflict with African worldviews.

If Africa continues to depend entirely on Western models, it will inherit not only the technological frameworks but also the biases, blind spots, and hidden ideological assumptions embedded within those models. These systems were not built with African cosmologies, social structures, languages, ancestral knowledge, ecological rhythms, or philosophical foundations in mind. They were built for other civilisations, with different historical experiences and different approaches to reasoning.

The Visionary Prompt Framework aspires to correct this structural dependency. Its Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber ensures that Africa’s knowledge systems sit at the centre of AI reasoning rather than at the margins. It provides an epistemological foundation upon which Africa can build an Intelligence Economy defined by African logic, African ethics, African cosmologies, and African aspirations.

This is not merely symbolic. It is essential for sovereignty.

Countries become truly sovereign not when they consume intelligence but when they generate it. Sovereignty in the 21st century is not only territorial or political but also cognitive. A nation is only as independent as the intelligence systems it builds, controls, and governs. The VPF provides this path by enabling each African country to integrate its indigenous knowledge systems into national AI models without compromising ancestral custodianship.

The roll-out of VPF across the continent, beginning in Ghana, represents a continental awakening. It is the recognition that Africa cannot build a future on imported knowledge systems alone. It must embrace the full spectrum of its historical, cultural, ecological, spiritual, scientific, and ancestral knowledge. This does not reject global science; it expands it. This does not oppose Western models; it completes what they have omitted.

The Ministry of Communication, Digital Technology and Innovation in Ghana has demonstrated continental leadership in recognising this vision. Through the launch of the Ghanaian AI Prompt Bible in August 2025, and the inauguration of the AiAfrica Labs for Ministries, Departments, Agencies and Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, Ghana has signalled that African-led intelligence systems must govern African digital futures. The first training programme that brought together 200 experts from government institutions introduced the concept of intelligence orchestration, demonstrating how indigenous and ancestral knowledge can be embedded in modern AI systems for governance and public service transformation.

The continental training strategy that follows in 2026 and beyond seeks to reach public institutions, universities, private companies, research centres, and development agencies across all 54 African countries. The vision is clear. African governments must not simply use AI. They must define what intelligence means in their own societies and govern AI according to indigenous principles of relationality, intergenerational ethics, communal harmony, and the custodianship of land and life.

The Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber offers a blueprint for this transformation. It provides the philosophical grounding, epistemic structure, cultural legitimacy, and operational methodology to build a truly African Intelligence Economy.

- The Limitations of Western AI in the African Context

It is essential to explain why Western AI models cannot be the sole foundation for Africa’s digital future. These models are not neutral. They reflect the values, priorities, economic structures, and historical trajectories of the societies that created them. Their strengths are substantial, but their limitations become clear when applied uncritically to African realities. Western AI assumes that knowledge is primarily textual. African societies often encode knowledge through oral tradition, symbolic structures, performance, ritual, genealogy, and land-memory. Western AI assumes that intelligence is individualistic. African societies operate through communal logic, collective responsibility, and shared identity. Western AI assumes that prediction is superior to perception. Indigenous intelligence values intuitive awareness, spiritual insight, ancestral continuity, and ecological relationality. Western AI assumes a mechanistic worldview that separates nature from human life. African knowledge systems recognise nature as a living partner in cognition.

These differences are not ideological preferences but foundational epistemic divergences. When Western AI is applied to African realities without adaptation, it produces distorted outputs, flawed recommendations, and solutions that lack cultural fit. A model that cannot understand indigenous governance structures will provide poor advice on national cohesion. A model that cannot interpret ancestral ecological knowledge will misguide environmental policy. A model that cannot respect cultural protocols will produce development strategies that provoke resistance.

A model that cannot recognise spiritual legitimacy will misunderstand community decision processes. A model that cannot encode oral epistemology will fail to represent African histories accurately. This is why the VPF Planetary Version is an essential corrective. It does not reject Western AI but balances it with Indigenous Intelligence that Western systems cannot see.

- Reframing Intelligence for an African Future

The Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber does more than preserve cultural heritage. It expands the definition of intelligence itself. It insists that intelligence includes story, rhythm, ritual, symbol, intuition, cosmology, ethics, memory, empathy, and ecological sensitivity. It restores intelligence to its full complexity.

In the VPF, intelligence is not simply computation but a holistic activity that draws simultaneously from eight worlds. The Indigenous Chamber holds one of the deepest worlds. It contains spiritual jurisprudence, communal ethics, oral science, ecological observation, ancestral cosmology, and symbolic thinking systems that have guided African societies for thousands of years. This reframing empowers African innovators, policymakers, and researchers to build systems that align with African ways of reasoning. It allows AI development to emerge not from imitation of Western systems but from African intellectual traditions. It offers a path where future models built by African teams can perform not merely as replicas of GPT or Gemini, but as independent civilisational intelligence systems grounded in African cosmology.

- A Call to African Institutions, Startups, and Innovators

Africa cannot afford to remain a consumer of external intelligence systems. The continent must become a producer of sovereign intelligence and must embrace the Indigenous Chamber as a foundational tool. Every public institution and every private company deploying AI should integrate VPF reasoning frameworks to ensure cultural alignment, ethical grounding, and contextual accuracy.

Startups building AI products for agriculture, health, logistics, commerce, education, climate, finance, or security must incorporate indigenous knowledge to create solutions that truly reflect African realities. Universities must train students to think across ancestral and technological domains. Traditional authorities must collaborate with AI researchers to protect sacred knowledge while enabling structured integration of ancestral epistemologies into innovation ecosystems. Ministries and regulatory bodies must embed indigenous epistemology into digital governance frameworks to ensure sovereignty over data, knowledge production, and algorithmic influence. The Indigenous Chamber is not an optional addition. It is a requirement for African digital self-determination.

- The Broader Significance for the World

While the VPF is designed with Africa as the anchor, its implications extend globally. Western AI models struggle with cultural nuance, ecological prediction, spiritual reasoning, restorative justice, communal ethics, and symbolic interpretation. These are precisely the domains where Indigenous knowledge excels. In elevating Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence, Africa offers a gift to the world. It demonstrates that wisdom is not limited to written texts. It shows that civilisation is impoverished when it forgets the intelligence encoded in elderhood, ritual, land, and lineage. It reveals that modernity does not replace ancestral knowledge but is strengthened by it. The Indigenous Chamber represents a global corrective. It addresses the epistemic imbalance that has shaped AI development for the past two decades. It restores balance to knowledge production. It challenges the dominance of a single worldview. It offers humanity a richer and more complete understanding of what intelligence can be.

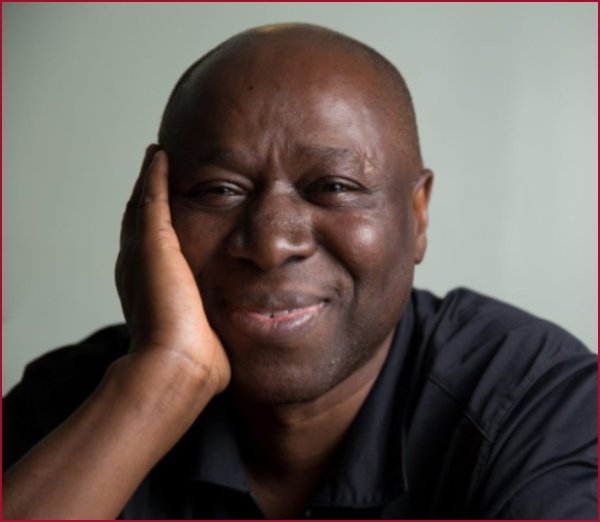

The author, Dr David King Boison is a Maritime and Port Expert, pioneering AI strategist, educator, and creator of the Visionary Prompt Framework (VPF), driving Africa’s transformation in the Fourth and Fifth Industrial Revolutions. Author of The Ghana AI Prompt Bible, The Nigeria AI Prompt Bible, and advanced guides on AI in finance and procurement, he champions practical, accessible AI adoption. As head of the AiAfrica Training Project, he has trained over 2.3 million people across 15 countries toward his target of 11 million by 2028.

Opinion

The Cocoa Conundrum: Why Ghana’s Farmers are Poor Despite Making the World’s Best Chocolate

Ghana produces some of the world’s finest cocoa beans, yet the majority of its cocoa farmers remain trapped in poverty due to low farmgate prices, exploitative supply-chain structures, middlemen taking large margins, high input costs, climate change impacts, illegal mining (galamsey) destroying farms, and limited access to credit and modern farming techniques. This article by H. Aku Kwapong argues that while multinational chocolate companies earn billions from Ghanaian cocoa, farmers receive only a tiny fraction of the final retail value, calling for urgent reforms in pricing, local processing, cooperative models, and government intervention to ensure fairer wealth distribution along the cocoa value chain.

The cocoa conundrum: Why Ghana’s farmers are poor despite making the world’s best chocolate

Every so often, you come across an economic situation so perverse, so utterly divorced from basic market logic, that you have to wonder how it has survived for so long.

The case of Ghana’s cocoa sector is a textbook example. Here we have a country that produces some of the world’s finest cocoa—the essential ingredient for a multi-billion dollar global chocolate industry. Yet the smallholder farmers who are the bedrock of this industry remain trapped in extreme poverty, many earning less than a dollar a day. How can this be?

The answer, as is so often the case, lies in a toxic mix of well-intentioned but misguided policy, institutional sclerosis, and a fundamental misunderstanding of how markets actually work. For over seven decades, Ghana has operated a state-run monopoly, the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD), that controls every aspect of the industry from farm gate to export. The result is a classic case of monopsony power, a single buyer that can dictate prices to sellers. And when a single buyer dictates prices, the sellers inevitably get a raw deal.

When cocoa prices quadrupled on the world market in 2023-2025, reaching nearly $12,000 per metric ton, Ghanaian farmers should have seen a windfall. They didn’t. Because of COCOBOD’s byzantine system of forward contracts and price-fixing, they were locked into prices that bore no resemblance to market reality. The very system designed to protect them from volatility ended up shielding them from prosperity. It’s an economic tragedy, and it’s long past time to end it.

This report is not an academic exercise. It is a call for a pragmatic, clear-eyed revolution in how Ghana manages its most important agricultural sector. It lays out a framework for dismantling a failed state monopoly and building a modern, competitive market in its place.

This isn’t about blind faith in laissez-faire economics—the history of commodity markets is littered with the victims of chaotic, unsupported liberalization. Instead, it’s about getting the institutions right, creating what I call a “meso-model” where a lean, effective government regulates a dynamic private sector. It’s about finally letting the market work for, not against, the people who make it possible.

1.The Economics of a Broken System

Let’s be clear about the diagnosis. Ghana’s cocoa problem isn’t a mystery; it’s a straightforward story of bad economics compounded by institutional inertia.

The current model, where COCOBOD acts as the sole buyer and seller of cocoa, is a relic of a bygone era of state-led development that most of the world has moved beyond. Its defenders will point to the premium quality of Ghanaian cocoa as justification for the system. And yes, the quality is good. But at what cost?

The Monopsony Trap

Here’s the fundamental problem: COCOBOD’s monopoly on purchasing cocoa from farmers means it faces no competition. Basic economics tells us what happens when a buyer has monopsony power – it can, and does, pay a price far below what a competitive market would deliver. Farmers in Ghana typically receive around 55% of the Free on Board (FOB) export price for their beans. Compare that to the 70-75% received by their counterparts in the more liberalized markets of Indonesia and Ecuador.

That 15-20 percentage point difference isn’t just a number on a spreadsheet. For a farming family, it’s the difference between a living income and grinding poverty. It’s the difference between being able to afford fertilizer and watching your trees succumb to disease. It’s the difference between sending your children to school and sending them to work in the fields.

And let’s be honest about what’s happening to that missing 40-45% of the export value. Some of it goes to legitimate costs – quality control, research, extension services. But a large chunk disappears into the maw of an inefficient, bloated bureaucracy that employs thousands of people and operates subsidiaries that would make a Soviet-era ministry proud.

The Illusion of Stability

The great promise of the COCOBOD system was price stability. By selling the crop forward on international markets, it was supposed to shield farmers from the notorious volatility of commodity prices. This sounds good in theory. In practice, it’s been a disaster.

The 2023-2025 price crisis exposed the fundamental flaw in this approach. When world cocoa prices exploded due to supply shortages in West Africa, the forward-selling system didn’t just fail to deliver the upside to farmers – it nearly bankrupted COCOBOD itself, which found itself on the wrong side of its own hedges. The institution recorded massive losses while farmers continued to receive their fixed, below-market prices.

This is the perverse logic of the current system: it privatizes the risks (which farmers bear through chronically low prices) and socializes the losses (which the state, and ultimately the taxpayer, has to cover). It’s heads the middlemen win, tails the farmers lose.

The Stagnation Effect

When you insulate an entire industry from market signals, you get stagnation. There is no incentive for innovation, no drive for efficiency, no pressure to improve. Why should a private company invest in better logistics or processing facilities if it can’t compete on price? Why should a farmer invest in higher quality beans or replant aging trees if they get paid the same as everyone else regardless of quality?

The result is an industry operating far below its potential. Production has collapsed from over 1 million tonnes in 2010/11 to just 654,000 tonnes in 2023 – a 14-year low. The tree stock is aging, with an estimated 40% of cocoa trees past their productive prime. The farming population itself is aging, with an average age over 50, as young people flee for better opportunities, including the destructive illegal gold mining (‘galamsey’) that is eating away at cocoa farmland.

This is what happens when you try to run an agricultural sector like a command economy. You get all the inefficiency of central planning with none of the dynamism of a market.

So the argument that we must choose between the chaos of a fully free market and the stagnation of a state monopoly is a false dichotomy. The real task is to design a system that combines the dynamism of competition with the stability of smart regulation. That’s what I mean by a “meso-model,” and that’s what the rest of this report is about.

2.Learning from Others: The Liberalization Spectrum

Before we dive into the specifics of reform, it’s worth looking at what has happened in other cocoa-producing countries that have experimented with different models. The evidence is actually quite instructive.

The Cautionary Tale of Full Liberalization

Nigeria liberalized its cocoa market in 1986, dismantling its marketing board and letting the market rip. The results were mixed at best. On the positive side, competition increased, more private traders entered the market, and farmers gained more options for selling their cocoa. Production initially increased as farmers responded to better price signals.

But there was a dark side. The abolition of the marketing board led to a collapse in quality control and extension services. Nigerian cocoa, once renowned for its quality, saw its reputation deteriorate as beans of varying quality flooded the market. Farmers lost access to credit and inputs that the marketing board had previously provided. And the market became dominated by a handful of large export firms, which used their oligopsony power to squeeze farmers.

The lesson here is clear: simply smashing the state monopoly and walking away is not a recipe for success. Markets need institutions to function properly.

The Ivorian Alternative

Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s largest cocoa producer, offers a more promising model. After its own chaotic liberalization in the 1990s, the country established a hybrid system built around the Conseil du Café-Cacao (CCC), a regulatory body that works in partnership with the private sector.

Here’s how it works: The CCC sets a guaranteed minimum price for farmers at the beginning of each season, providing a safety net against price crashes. But it also licenses private companies to compete in buying and exporting cocoa. These companies can offer bonuses above the minimum price for higher quality beans or faster payment. The result is a system that provides both stability and competition.

The Ivorian model isn’t perfect – it still involves significant state intervention, and there are concerns about corruption and the fiscal costs of the price guarantee. But it has managed to maintain quality standards while allowing for private sector dynamism. Production has grown steadily, and farmers receive a higher share of the export price than their Ghanaian counterparts.

What Ghana Can Learn

The lesson from this comparative analysis is straightforward: Ghana needs to move away from its current fully regulated model, but it should not leap to full liberalization. The optimal path is a middle ground – a “meso-model” that retains essential state functions (regulation, quality control, research) while introducing competition in commercial activities (buying, processing, exporting).

This is not a radical idea. It’s basically what most successful agricultural sectors around the world do. The government sets the rules and provides public goods; the private sector competes to deliver services and create value. It’s time Ghana joined the 21st century.

3.The Reform Framework: Eight Pillars for a New Dawn

So what does a sensible reform program look like? It rests on eight interconnected pillars, each addressing a specific dysfunction in the current system. Let me walk through them.

Pillar 1: Transforming COCOBOD from Monopolist to Regulator

The first and most critical step is to fundamentally restructure COCOBOD. The institution needs to go on a serious diet, shedding its commercial functions and focusing on the essential public goods that only government can provide.

What COCOBOD Should Keep:

•Quality Control: This is a genuine public good and a crucial national asset. Ghana’s reputation for premium cocoa is worth protecting, and a centralized quality control system is the best way to do it. The Quality Control Company (QCC) should remain under COCOBOD’s umbrella, ensuring that all exported cocoa meets high standards.

•Research and Development: The Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana (CRIG) has done valuable work developing high-yielding, disease-resistant varieties. This is exactly the kind of basic research that the private sector tends to under-invest in. CRIG should continue to receive public funding and should be encouraged to partner with universities and international research institutions.

•Regulation: Someone needs to set the rules for a competitive market – licensing buyers and exporters, monitoring for anti-competitive behavior, ensuring traceability and compliance with international standards. This is a core government function.

What COCOBOD Should Lose:

•Internal Marketing: The business of buying cocoa from farmers should be opened to competition among Licensed Buying Companies (LBCs), farmer cooperatives, and processing companies. Let them compete on price, payment terms, and services. The farmers will benefit.

•Input Supply: The procurement and distribution of fertilizers and pesticides should be handled by private agro-dealers. The current system of heavily subsidized inputs distributed through COCOBOD is costly, inefficient, and subject to political manipulation. A competitive market for inputs, perhaps supported by targeted vouchers for the poorest farmers, would work better.

•Export Marketing: The Cocoa Marketing Company (CMC), which currently has a monopoly on exports, should either be privatized or forced to compete with other licensed exporters. This would allow for more innovative marketing arrangements and better price discovery.

This transformation will not be easy. It will require significant downsizing and restructuring. COCOBOD currently employs thousands of people; a lean regulatory body would need far fewer. A comprehensive staff rationalization plan, including voluntary retirement schemes and retraining programs, will be essential. But the alternative is the slow-motion collapse of the entire institution, which helps no one.

Pillar 2: Creating Space for Private Enterprise

Once COCOBOD gets out of the way, private companies can step in to compete across the value chain. But they won’t do so unless the government creates an enabling environment. This means three things:

Regulatory Certainty: Investors need to know that the rules won’t change overnight. A clear, transparent, and stable regulatory framework is essential. This includes straightforward licensing procedures, well-defined quality standards, and consistent enforcement.

Infrastructure: You can’t build a competitive industry on crumbling roads and unreliable electricity. The government needs to invest in the basics – farm-to-market roads, port facilities, warehousing, and above all, reliable and affordable power. The fact that electricity costs in Ghana are nearly double those in Côte d’Ivoire is a major barrier to developing a domestic processing industry.

Targeted Incentives: To encourage investment in value addition – turning raw beans into cocoa liquor, butter, powder, and finished chocolate – the government should offer tax holidays, reduced import duties on processing equipment, and perhaps subsidized electricity for processing facilities. The goal is to move Ghana up the value chain, capturing more of the value that currently goes to processors in Europe and Asia.

The potential here is enormous. Ghana currently processes only about 23% of its cocoa production domestically, and existing facilities operate at less than 50% capacity. With the right policies, Ghana could become a major exporter of processed cocoa products and even build globally recognized chocolate brands. Companies like Fairafric are already showing what’s possible.

Pillar 3: Fixing the Price Mechanism

The current pricing system is, to put it bluntly, a joke. It’s opaque, it’s rigid, and it systematically underpays farmers. The Producer Price Review Committee (PPRC) sets a fixed price at the beginning of each season based on projections that often turn out to be wildly wrong. Farmers have no idea how the price is calculated, and they have no recourse if they think it’s unfair.

This needs to be replaced with a transparent, market-based system. There are several options:

Auction System: Cocoa could be sold through regular auctions where buyers bid competitively for lots. This ensures transparent price discovery and allows farmers to benefit directly from market prices. Ethiopia’s commodity exchange provides a successful model.

Commodity Exchange: The proposed Africa Commodity Exchange (AfCX) could provide a pan-African platform for trading cocoa, with prices determined by supply and demand.

Direct Contracts: Farmers and cooperatives could negotiate direct contracts with buyers, allowing for differentiated pricing based on quality, volume, and delivery terms.

Hybrid Model: My preferred option is a hybrid approach that combines a guaranteed minimum price (a floor) with market-based pricing above that level. This is similar to Côte d’Ivoire’s model. The floor provides security against price crashes, but farmers can earn more if they produce higher quality beans or if market conditions are favorable.

The key principle is simple: farmers should receive at least 70% of the FOB export price. This isn’t charity; it’s basic market efficiency. Farmers who are paid a fair price will invest in their farms, leading to higher production and better quality. Everyone wins.

Of course, a market-based system means price volatility. But there are sensible ways to manage this risk. A price stabilization fund can smooth out fluctuations by saving money in good years to support prices in bad years. Crop insurance can protect farmers from severe price drops. And over time, as farmers and cooperatives gain experience, they can use financial instruments like futures contracts to hedge their own risk.

Pillar 4: Building a Real Processing Industry

Here’s a shocking fact: Ghana captures only about 6.6% of the total value of its cocoa production. The rest – the vast majority—is captured by processors and manufacturers in

Europe, North America, and Asia. This is economic madness. Ghana is exporting raw materials and importing finished products, exactly the colonial pattern that developing countries are supposed to have moved beyond.

The solution is to dramatically expand domestic processing capacity. Ghana already has several major processing facilities, but they operate at less than 50% capacity because they can’t get enough beans. In the current system, COCOBOD’s forward sales contracts commit most of the crop to international buyers, leaving domestic processors scrambling for supply.

In a liberalized market, processors would be able to source beans directly from farmers. But during the transition, the government should guarantee that a certain percentage of production, say, 30-40%, is reserved for domestic processors at competitive prices. This would ensure that processors can operate at full capacity.

The barriers to processing are well-known: high energy costs, limited access to finance, and a shortage of skilled workers. Each of these can be addressed with targeted policies:

•Energy subsidies for processing facilities to offset Ghana’s high electricity costs.

•Tax incentives, including corporate tax holidays and duty-free imports of processing equipment.

•Dedicated financing facilities, perhaps through a Cocoa Development Bank, to provide long-term, affordable credit.

•Skills development programs in partnership with technical universities and international training institutions.

Beyond semi-processed products, Ghana should aim to build its own chocolate manufacturing industry and develop globally recognized Ghanaian chocolate brands. The market for premium, single-origin, ethically sourced chocolate is growing rapidly. Ghanaian brands can capitalize on the country’s reputation for quality, its sustainability credentials, and its unique cultural heritage. With the right support, “Made in Ghana” chocolate could become a premium product on the world market.

Pillar 5: Empowering Farmers Through Cooperatives and Land Reform

Individual smallholder farmers have essentially no bargaining power when facing large buyers. This is why strong, well-organized farmer cooperatives are essential. Cooperatives can negotiate collectively, secure better prices, access credit, and provide services to their members.

Ghana has a history of farmer cooperatives, including the well-known Kuapa Kokoo, a Fairtrade cooperative with over 100,000 members. But many cooperatives suffer from weak governance, poor financial management, and limited capacity. They need support, training in governance and financial management, access to credit, and a clear legal framework that protects their rights.

In a liberalized market, cooperatives should be able to negotiate directly with buyers and processors on behalf of their members. This collective bargaining power is the best defense against exploitation.

But there’s an even more fundamental issue: land tenure. Many cocoa farmers in Ghana don’t have secure title to the land they farm. Under the traditional Customary Land Tenure System, they have only usufruct rights – the right to use the land but not to own it. This creates a massive disincentive to long-term investment.

Why would you cut down old, unproductive trees and replant if you’re not sure you’ll still have the land in five years when the new trees start producing? Why would you invest in soil improvement or irrigation if you could lose the land at any time? And without formal title, you can’t use your land as collateral for a loan.

This is a politically sensitive issue, involving traditional authorities and complex customary law. But it must be addressed. Options include formalizing long-term leases, providing legal protections for farmers who replant, and gradually introducing formal land titling in cocoa- growing regions. Women farmers, who often have even more insecure land rights than men, need special attention.

Pillar 6: Leveraging Technology

We live in the 21st century, but much of Ghana’s cocoa sector operates as if it’s still the 20th. Technology can change this, and it doesn’t require massive investments in fancy equipment. Simple, accessible technologies can make a huge difference.

Mobile Payments: Ghana already has widespread mobile money platforms like MTN Mobile Money. Extending these to cocoa payments would mean farmers get paid immediately upon delivery, with a digital record that reduces disputes and fraud. It would also give farmers access to savings and credit products linked to their mobile wallets.

Digital Extension Services: Mobile apps and SMS platforms can deliver timely advice on weather, pest control, best practices, and market prices. The Cocoa Link program has already demonstrated the potential of this approach.

Traceability Systems: The EU Deforestation Regulation now requires full traceability of cocoa imports. Digital systems using GPS mapping and mobile data collection can help Ghanaian farmers comply with these requirements and access premium markets. This isn’t optional anymore; it’s a necessity.

And here’s the thing: attracting young people back to cocoa farming requires making it less of a backbreaking, low-tech drudgery and more of a modern, tech-enabled business. Higher incomes are part of the answer, but so is modernization.

Pillar 7: Building the Regulatory Architecture

A liberalized market needs a strong regulatory framework. The current system, where COCOBOD is both player and referee, is fundamentally flawed. Ghana needs an independent Cocoa Regulatory Authority (CRA) that is separate from COCOBOD and reports to Parliament rather than to a government ministry.

The CRA’s job would be to:

•License buyers, processors, and exporters.

•Set and enforce quality standards.

•Monitor the market for anti-competitive behavior.

•Resolve disputes between farmers and buyers.

•Oversee traceability and compliance with international regulations.

Ghana also needs to strengthen its competition law and apply it rigorously to the cocoa sector to prevent price-fixing and market manipulation. And it needs a clear legal framework for contracts, with fast-track arbitration and mediation services for disputes.

The goal is to create a level playing field where companies compete on efficiency and service, not on political connections or market manipulation.

Pillar 8: Financing the Transition

For decades, Ghana’s cocoa sector has been financed through an annual syndicated loan arranged by COCOBOD, typically in the range of $1.5-2 billion. This model is no longer sustainable. The cost of the loan has risen sharply, and COCOBOD has struggled to service its debt.

A liberalized sector needs a diversified financing ecosystem:

•Commercial bank lending to LBCs, processors, and farmer cooperatives.

•Warehouse receipt financing, which allows farmers to use stored cocoa as collateral for loans.

•Supply chain finance, where buyers provide advance payments to farmers in exchange for guaranteed supply.

•Microfinance and impact investing for small farmers and businesses.

•A Cocoa Development Bank to provide long-term, affordable credit for the sector.

The Ghana Stock Exchange could also play a role, with large processors and LBCs listing to raise equity capital, and cocoa-backed bonds to finance infrastructure.

The key is to move away from the current model where the entire sector depends on a single, increasingly expensive loan, and toward a system where financing flows from multiple sources based on commercial viability.

4.The Politics of Reform: Why This Is Hard (But Necessary)

Let me be blunt: the economics of cocoa reform are straightforward. The path to a more prosperous and competitive sector is clear. The real challenge, as always, is politics.

Any serious reform will threaten entrenched interests that benefit from the current system. COCOBOD employs thousands of people, many of whom will resist downsizing. The current system creates opportunities for rent-seeking and corruption that will be harder to maintain in a competitive market. And there’s a genuine, if misguided, ideological attachment to the idea of state control among some policymakers.

There will be resistance. There will be scare stories about how liberalization will lead to chaos and exploitation. There will be warnings that Ghana will lose its quality premium. These arguments need to be confronted head-on with evidence and clear communication.

This is why the transition must be carefully managed, with a clear roadmap, strong governance, and constant engagement with all stakeholders. A “big bang” approach is likely to fail, as Nigeria’s experience shows. A phased, 5-10 year transition, with clear milestones and measurable targets, is the only realistic way forward.

Phase 1 (Years 1-2): Establish the legal framework, launch pilot programs in selected regions, begin COCOBOD restructuring.

Phase 2 (Years 3-5): Roll out liberalized internal marketing nationwide, operationalize the CRA, introduce market-linked pricing, implement processing incentives.

Phase 3 (Years 6-10): Complete export liberalization, finish COCOBOD transformation, achieve 70% farmer share target, reach 40% domestic processing target.

Success will require political courage and long-term vision. It will require resisting the temptation to backslide when things get difficult. And it will require constant monitoring and adjustment, because no reform plan survives first contact with reality unchanged.

But the alternative is to continue presiding over a system that is failing its farmers, failing the nation, and slowly collapsing under the weight of its own contradictions. The choice is stark, but it is also clear.

5.Conclusion: The Case for Optimism

I am, by temperament and training, a skeptic. I’ve seen too many grand reform plans fail, too many well-intentioned policies produce perverse outcomes. But I’m also an economist, and I believe that when you get the incentives right, when you build the right institutions, good things can happen.

Ghana’s cocoa sector is broken, but it’s not beyond repair. The country has enormous advantages: a reputation for quality, a large and experienced farming population, existing

processing infrastructure, and a strategic location. What it lacks is a sensible institutional framework that allows these advantages to be fully realized.

The reform framework laid out in this report is not utopian. It’s pragmatic, evidence-based, and grounded in the real-world experiences of other countries. It doesn’t require Ghana to become something it’s not; it requires Ghana to become a better version of itself.

If implemented with determination and skill, these reforms could transform Ghana’s cocoa sector from a struggling commodity exporter into a globally competitive industrial powerhouse. Farmers could earn a decent living. Young people could see a future in agriculture. Ghana could capture more of the value from its most important export crop.

This is not just about cocoa. It’s about whether Ghana can build the kind of modern, market- based institutions that are essential for sustained economic development. It’s about whether the country can move beyond the legacy of colonialism and state-led development to create a system that works for its people.

The time for a new dawn for Ghana’s cocoa is now. The question is whether Ghana’s leaders are ready to seize it.

By: H. Aku Kwapong Hene Aku Kwapong can be reached on oak@songhai.com. He is a founder of The Songhai Group and NBOSI (National Blue Ocean Strategy Institute). He formerly worked with GE Capital, Deutsche Bank and Royal Bank of Scotland and had been a Senior Vice President at the New York City Economic Development Corporation.

Opinion

Nkrumahism, Mahama, and Africa’s unfinished cultural liberation

President Mahama’s recent state visit to Zambia and his advocacy for local languages in education embody the core principles of Nkrumahism, advancing Africa’s unfinished cultural liberation by challenging colonial legacies and promoting continental unity and self-reliance. The article by Dr. Manaseh Mawufemor Mintah, calls for rejecting mental colonization—seen in lingering Eurocentric norms, foreign attire, and institutional dependencies—urging Africans to reclaim their identity, history, and narrative control in the spirit of Nkrumah’s vision for a truly independent continent.

The buzz, anger, and friendly debate over President Mahama’s official visit to Zambia this week has opened the door for something far more important than travel diplomacy. It has allowed us to begin a serious national and continental conversation about Africa’s future, its sustainability, and, more importantly, its identity.

President Mahama’s rectilinear path to Zambia fits neatly into the Nkrumahist agenda. That agenda envisioned an integrated African society that co-exists as a union, speaks with one voice, removes the artificial barriers imposed by colonialism, trades among itself, and presents a strong bargaining position on the global stage over its own resources, culture, and people. That vision was not romantic idealism. It was a strategic necessity.

Yet, even before these aspirations could begin to gather momentum, the reaction from parts of Zambian society mocked the very idea. That response, unfortunate as it was, stands as a living testament to the prolonged and corrosive effects of slavery, colonialism, and neo-colonialism, what Nkrumah correctly described as the last stage of imperialism.

Today, we gloat in colonial attire. Our politicians revere taking pictures in European suits and proudly post them on social media, celebrating their great looks in a white man’s costume. At the same time, we look at our own local fabrics and traditional costumes with suspicion and derision. Once someone controls your mind and your narrative, your body becomes nothing more than an appendage. We name our children after Greco-Roman gods and celebrate Jewish names as divine, yet dismiss our own African names as fetish. This is the tragedy of mental colonization. Wodemaya, I am glad, has stated this clearly in his ecclesiastical response to the Zambians.

Africa is not alone in this experience. Long before America’s cultural maturity from Great Britain, America was trapped in the same shadows. In his seminal essay “The American Scholar,” Ralph Waldo Emerson asked a piercing question that awakened the American consciousness: “For how long shall we feed on the remains of foreign harvests?” That single line forced a new nation to plant itself on its own instincts. In another essay, “Self-Reliance,” Emerson went further, calling for nothing short of a cultural revolution.

Emerson was not merely delivering a speech. He was issuing a declaration of cultural independence. Politically, America had broken from Britain in 1776.

Culturally and intellectually, it had not. Before Emerson, American thinkers quoted British philosophers as final authorities, imitated British literary styles, and treated Europe as the intellectual center of the world. Emerson rejected this outright. He urged Americans to trust their own minds, think from lived experience, and stop being parrots of other men’s thinking. That moment marked a decisive break from British epistemic hierarchy.

America went further. It dropped British Victorian architecture and invented the American house. Frank Lloyd Wright built on the prairies, designing architecture informed by landscape and geography rather than European imitation. The new nation abandoned the fear of being unfinished Europeans. It dropped British costumes and rigid social organization. This cultural liberation produced free thinkers like Daniel Webster and others who helped shape American English and American political thought.

Africa must learn from this history. African ideas and thoughts cannot continue to exist as footnotes to Eurocentric worldviews. We cannot sit idly while Europeans tell us they discovered the Volta or the Zambezi. We cannot continue naming our waterfalls after Livingstone, our cities, and institutions after the Queen of England. Africa has its own history, its own memory, and its own way of life. This was part of the reason Nkrumah brought in W.E.B Du Bois to collect and put together the Encyclopedia Africana.

In this light, our courts cannot continue quoting Lord Mansfield and William Blackstone as if legal intelligence depends on British approval. That does not make one intelligent. It makes one a puppet of Eurocentric thought. The same applies to how we see ourselves as Africans.

After living in America for sixteen years, I dropped my English name and maintained my Africanness. I did this as a reverence to my ancestry and as a deliberate act of distinction. I am not a Jewish man, nor am I European. While European history traces its origins to Greece and Rome, African thought and civilization began in Egypt and Ethiopia. That distinction matters. I stopped wearing suits long ago. I do not gloat in European costumes, nor do I parade the English language as the sole language of civilization. This is the point President Mahama understands, and which many of our so-called educated elite and even some clergy fail to grasp.

Recently, I heard Pastor Otabil argue for the continued dominance of English as the language of instruction in our classrooms, suggesting that English has traveled far and is necessary for validation. I strongly disagreed. People without identity are lost forever in the quicksand of history, and that is why I applaud President Mahama for his policy to use local languages as languages of teaching and instruction in the classroom.

This moment must go far beyond Zambia. It must translate into a national awakening and a conscious process of decolonization. Our scholars, many of whom have an unhealthy penchant for everything European, must be re-schooled. Our parliamentarians must abandon foreign attire. Our lawyers and judges must drop colonial wigs. Our institutions must be renamed after local histories. Our streets, rivers, and iconic landmarks must reflect African culture and identity. There are no other roads.

The writer, Dr. Manaseh Mawufemor Mintah, is an Afrocentric environmental and legal scholar based in Boston, Massachusetts. He can be reached at mmintah@antioch.edu.

Opinion

Borderless Africa: The Reparations Africa Owes Herself

In this opinion feature, authors Hardi Yakubu and Eunice Odhiambo argue that the artificial borders imposed during the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference remain a profound colonial wound, dividing ethnic groups, separating families (as illustrated by the story of two Ewe men named Enam on opposite sides of the Ghana-Togo border), and perpetuating intra-African trade barriers, visa restrictions, and economic fragmentation while ironically easing access for foreign powers. The writers contend that true reparations Africa owes itself lie not in demanding compensation from former colonizers, but in dismantling these borders to restore pre-colonial unity and harness the continent’s collective potential.

Read the full article below:

Borderless Africa: The reparations Africa owes herself

Story from Aflao: Two Enams, One People, Two Countries

In Aflao, on the Ghana–Togo border, we joined a community football match as part of our Borderless Africa community activities, Ghanaians on one side, Togolese on the other

We met several interesting people and discovered so much about life in border communities. Among the players were two young men from the opposite teams, both named Enam, which means “God has given”, a name common among the Ewe people.

They spoke Ewe fluently and understood each other perfectly. Interestingly, when the Ghanaian Enam spoke English, his Togolese counterpart could not understand, and when the Togolese Enam spoke French, the Ghanaian did not understand either.

They shared a name, a people, and family ties across the border, yet colonial languages and national identities branded them as foreigners. Their story is not unique it is repeated across Africa.

The Chewa, Ngoni, Tombuka and Ngonde are divided between Malawi and Zambia; the Mandinka, the Soninke between Mali and Senegal; the Wolof and the Serer between Gambia and Senegal, and so forth.

The story of the Ghanian and Togolese ‘Enams’ illustrates what is true of most African countries and what the colonial borders have done to African cultures, ethnicities, and even families.

The Colonial Carving of Africa

The artificial borders separating African people are part of the most enduring legacies of colonialism in Africa. These borders were not created by Africans.

They were sketched during the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference where European nations, without the participation of any African, sliced the continent into pieces with no regard for its people. Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister of the UK at the time, is quoted as saying.

“We have been engaged in drawing lines upon maps where no white man’s feet have ever trod; we have been giving away mountains and rivers and lakes to each other, only hindered by the small impediment that we never knew exactly where the rivers and lakes were”. They were aware of the damage they were doing.

Arbitrary lines on colonial maps split ethnic groups, merged rivals, and disrupted centuries-old patterns of life and created political units that served colonial interests rather than African realities. These borders remain a painful reminder that Africa’s political geography is a colonial inheritance, not an African design.

Colonial Borders; Daggers to the Soul

The colonial borders were more than lines on maps; they cut into the African soul. They separated families across borders, cut across ancient kingdoms and split them apart, they closed off communities from their own trade lines.

They interrupted the flow of culture, kinship, and commerce. They taught us to look on our brothers and sisters as foreigners but opened our gates to strangers more freely than to each other. The Berlin Conference did not just partition our land; it tore our humanity.

This tragedy continues today. It is easier for an American, Chinese, or European to conduct business in several African countries than it is for an African merchant to take a trip over a border to sell her merchandise.

As a result, intra-African trade has lagged behind – at a measly 14.9% according to the Africa Trade Report 2024.

A Kenyan requires a visa to access several African nations, but a French comes with utmost ease. Africa’s richest man, Aliko Dangote, famously pointed this out to his French counterpart during the Africa CEO Forum in 2024, the viral video clip from that has been circulating since then.

Africans have facilitated foreigners more than our own people to access our markets, our land, and our workforce, than Africans welcoming Africans.

Reparations

People of African descent across the world have been at pains to let the world acknowledge the harm that was caused to us through the evils of slavery and colonialism.

Reparations is simply about the repair of the past damage. It is a righteous call for acknowledgment of these crimes, for restitution and for compensation. Our demand for compensation is not far-fetched neither is it unprecedented.

It is a call to The Germans have paid and continue to pay reparations for the holocaust.

On the contrary, they have not done so for their genocide in Namibia except to pledge token so-called “development aid”.

The campaign for reparations has intensified with the African Union declaring it as the theme for the decade. The physical borders and their manifestations in our finance, economics, travel, culture etc are some of the most visible remnants of the colonial past. Removing them therefore is a crucial part of the repair.

But this part of the repair is within our power to do. Accepting responsibility for this does not detract from the responsibility of the perpetrators of the historical crimes for which reparations must be paid.

On the contrary it shows our willingness to embrace wholistic repair that counts on us to do our part to undo the damage that we have endured for centuries. The most significant of this is to give to ourselves a Borderless Africa.

Borderless Africa – Reparations within our power

We must complete the work our fore-fathers and foremothers started. They led us to regain our independence from the colonialists. So much blood and was shed. That political independence (no matter how nominal) puts the power in our hands to undo the borders that were created to divide and rule us.

Redress from the former colonialists is appropriate, but Africa owes herself one united and borderless republic. One currency and one central bank. One passport and one citizenship. One African army united under one command.

Congruent infrastructure, free movement of goods and people, and African systems of knowledge, values, and a renaissance of African indigenous languages – an Africa unbroken by the colonial languages, but unified through the Kiswahili, IsiZulu, Hausa, Luganda, Amharic, Lingala, and the many other African lingua fracas.

We can and should erase the colonial borders; physical and mental, and link Africa, as it originally was. Undoing Berlin 1884 is within our power to do as Africans. Thanks to our political independence (no matter how nominal), we do not need another roundtable by white people to decide for us what to do with the borders.

With enough political will and a people’s commitment, we can remove the borders. We are not saying this would be easy.

Many attempts have been made in the past in the spirit of Pan-Africanism, anchored in a long history of history from the Pan-African Congresses to the All-African Peoples Conferences, the Ghana-Guinea-Mali Union (1962), the Organization of African Unity (1963), the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) to the Senegambia Confederation (1985).

However, grounding this vision in the values of Ubuntu, that “I am because we are”; in Harambee, that call to unity; in Ujamaa, that value of familyhood and common prosperity; in Pan-Africanism, solidarity, self-determination, we can achieve it.

A Unified, Borderless Africa is in our interest

A borderless Africa would unlock immense potential, reconnecting communities divided by colonial lines and transforming the continent into a truly unified bloc. Free movement of people would allow Africans to travel, work, and live anywhere without restrictions, while open borders would boost trade, lower costs, and create one vast integrated market.

Shared management of resources and continental infrastructure projects would thrive, strengthening cooperation instead of conflict. For families like the Maasai, Ewe, and Somali, whose lives were split by arbitrary colonial maps, borderless living would mean cultural reconnection and dignity restored.

Beyond economics and culture, a united Africa would give Africa greater bargaining power on the global stage, shifting her from a continent fragmented by colonial design to one that speaks with a single, powerful voice.

A unified and borderless Africa vision is not a mirage. It is the agenda to defeat neo-colonialism and bring about the collective prosperity that we long for. The flags have been replaced, but the map still has the scars of Berlin.

We need to cure them, not with talk but with courage, creativity, and unity.

Borderless Africa is the reparation we owe ourselves. And we must pay it in our lifetime.

This opinion by Hardi Yakubu and Eunice Odhiambo was first published by GhanaWeb

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana News Live Updates: Catch up on all the Breaking News Today (Feb. 15, 2026)

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoThree Killed, Multiple Vehicles Burnt as Fuel Tanker Explodes on Nsawam-Accra Highway

-

Ghana News10 hours ago

Ghana News10 hours agoGhana News Live Updates: Catch up on all the Breaking News Today (Feb. 16, 2026)

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana is Going After Russian Man Who Secretly Films Women During Intimate Encounters

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoThe Largest Floating Solar Farm Project in West Africa is in Ghana: Seldomly Talked About But Still Powering Homes

-

Ghana News22 hours ago

Ghana News22 hours agoGhana Actively Liaising with Burkinabè Authorities After Terrorists Attack Ghanaian Tomato Traders in Burkina Faso

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSilent Turf War Intensifies: U.S. Extends AGOA, China Responds with Zero-Tariff Access to 53 African Nations

-

Taste GH1 day ago

Taste GH1 day agoOkro Stew: How to Prepare the Ghanaian Stew That Stretches, Survives, and Still Feels Like Home