Perspectives

How Maduro’s capture went down – a military strategist explains what goes into a successful special op

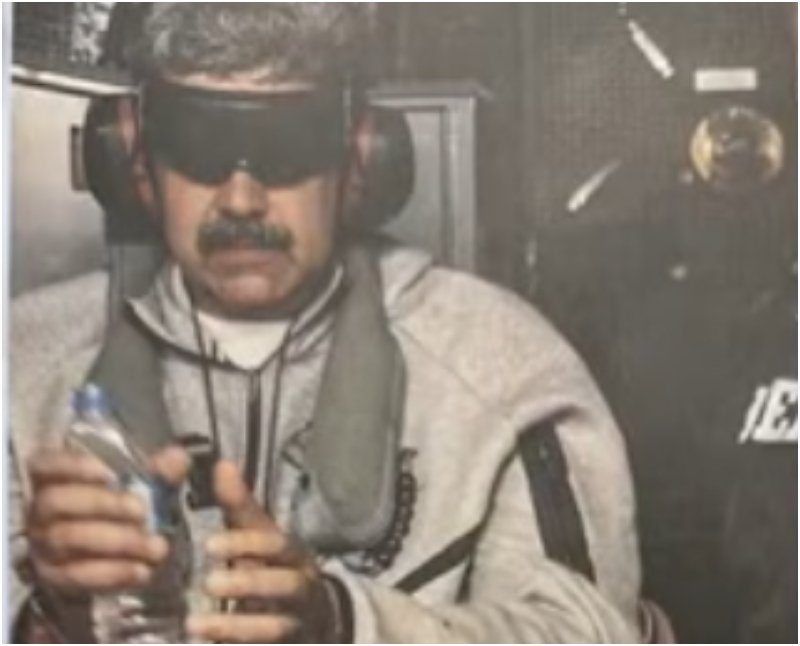

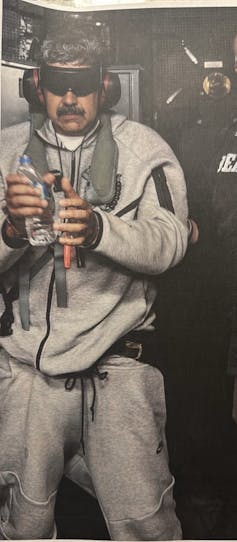

R. Evan Ellis, The Center for Strategic and International Studies, surmises in this article that the predawn seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on Jan. 3, 2026, was a complicated affair. It was also, operationally, a resounding success for the U.S. military.

Operation Absolute Resolve achieved its objective of seizing Maduro through a mix of extensive planning, intelligence and timing. R. Evan Ellis, a military strategist and former Latin America policy adviser to the U.S. State Department, walked The Conversation through what is publicly known about the planning and execution of the raid.

How long would this op have been in the works?

Operation Absolute Resolve was some months in the planning, as the Pentagon acknowledged in its briefing on Jan. 3. My presumption is that from the beginning of the U.S. military buildup in the Caribbean and the establishment of Joint Task Force Southern Spear in the fall, military planners were developing options for the president to capture or eliminate Maduro and other key Chavista leadership, should coercive efforts at persuading a change in the Venezuelan situation fail.

Prior to Southern Spear, U.S. military activities in the region were directly overseen by Southern Command – the part of the Department of Defense responsible for Central America, South America and most of the Caribbean. But establishing a dedicated joint task force in October 2025 helped facilitate the coordination of a large operation, like the one conducted to seize Maduro.

Planning for the Jan. 3 operation likely became more detailed and realistic as the administration settled on a concrete set of options. U.S. forces practiced the raid on a replica of the presidential compound. “They actually built a house which was identical to the one they went into with all the same, all that steel all over the place,” President Donald Trump told “Fox & Friends Weekend.”

Why did the US choose to act now?

The buildup had been going on for months, and the arrival of the USS Gerald R. Ford in November was a key milestone. That gave the U.S. the capability to launch a high volume of attacks against land targets and added to the already huge array of American military hardware stationed in the Caribbean.

It joined an Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group, which included a helicopter dock ship and two landing platform vessels. An additional six destroyers and two cruisers were stationed in the region with the capability of launching hundreds of missiles for both land attack and air defense, as well as a special operations mother ship.

Trump’s authorization of CIA operations in Venezuela was probably also a key factor. It is likely that individuals inside Venezuela played invaluable roles not only in obtaining intelligence, but also in cooperating with key people in Maduro’s military and government to make sure they did – or did not do – certain things at key moments during the Jan. 3 operation.

With the complex array of plans and preparations in place by December, the U.S. military was likely ready to execute, but it had to wait for opportune conditions to maximize the probability of success.

What constitutes the opportune moment?

There are arguably three things needed for the opportune moment: good intelligence, the establishment of reliable cooperation arrangements on the ground, and favorable tactical conditions.

Intel would have been crucial. Trump acknowledged his authorization of covert CIA operations in Venezuela in October, and evidently, by the end of the year, analysts had gathered the information needed to make this operation go smoothly. The intelligence would have had to include knowing exactly where Maduro would be at the time of the operation, and the situation around him.

Over the past few months, according to media reporting, the intelligence community had agents on the ground in Venezuela, likely having conversations with people in the military, the Chavista leadership and beyond, who had crucial information or whose behavior was relevant to different parts of the operation – such as perhaps shutting down a system, standing down a military unit or being absent from a post at a key moment. A report from The New York Times indicates that the U.S. had a human source close to Maduro who was able to provide details of his day-to-day life, down to what he ate.

The more tactical conditions that were needed for the opportune moment involved things like the weather – you didn’t want storms or high winds or cloud cover that would put U.S. aircraft in danger as they flew in some very treacherous low-level routes through the mountains that separate Fort Tiun – the military compound in Caracas where Maduro was captured – from the coast.

How did the operation unfold?

Gen. Dan Caine, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has given some details about how the plan was executed.

We know the U.S. launched aircraft from multiple sites – the operation involved at least 20 different launch sites for 150 planes and helicopters. These would have involved aircraft for jamming operations, some surveillance, fighter jets to strike targets, and some to provide an escort for the helicopters bringing in a special forces unit and members of the FBI.

As an integral part of the operation, the U.S. carried out a series of cyber activities that may have played a role in undermining not only Venezuela’s defense systems, but also its understanding of what was going on. Although the nature of U.S. cyber activities is only speculation here, a coherent, alerted Venezuelan command and control system could have cost the lives of U.S. force members and given Maduro time to seal himself in his safe room, creating a problem – albeit not an insurmountable one – for U.S. forces.

There was also, according to Trump, a U.S.-generated interruption to some part of the power grid. In addition, it appears that there may have been diversionary strikes in other parts of the country to give a false impression to the Venezuelan military that U.S. military activity was directed toward some other, lesser land target, as had recently been the case.

U.S. aircraft then basically disabled Venezuelan air defenses.

As U.S. rotary wing and other assets converged on the target in Caracas – with cover from some of the most capable fighters in the U.S. inventory, including F-35s and F-22s, as well as F-18s – other U.S. assets decimated the air defense and other threats in the area.

It would be logical if elite members of the U.S. 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment were used in the approach to the compound in Caracas. Their skills would have been required if, as I presume, they came in via the canyon route that separates Caracas from the coast. I have driven the road through those mountains, and it is treacherous – especially for an aircraft at low altitude.

Once the team landed, it would have have taken a matter of minutes to infiltrate the compound where Maduro was.

Any luck involved?

According to Trump, the U.S. team grabbed Maduro just as he was trying to get into his steel vault safe room.

“He didn’t get that space closed. He was trying to get into it, but he got bum-rushed right so fast that he didn’t get into that,” the U.S. president told Fox & Friends Weekend.

Although the U.S. was reportedly fully prepared for that eventuality, with high-power torches to cut him out, that delay could have cost time and possibly lives.

It was thus critical to the U.S. mission that forces were able to enter the facility, reach and secure Maduro and his wife in a minimal amount of time.

R. Evan Ellis, Senior Associate, Americas Program, The Center for Strategic and International Studies

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Commentary

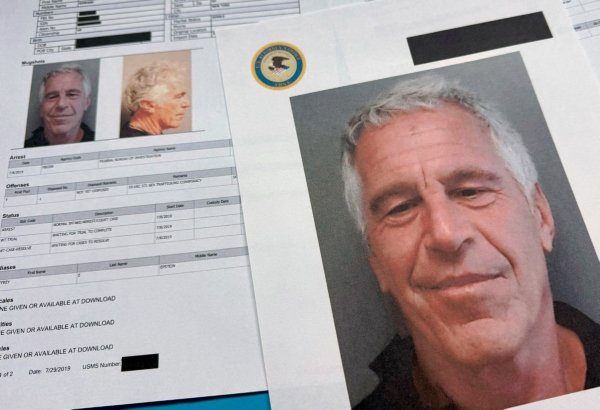

There Is New Convincing Theory on Why Epstein’s Death Might Be a Grand Cover Up

A new online theory circulating this week has reopened long-standing doubts about the death of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein — this time centering on a medical discrepancy involving his prostate.

The claim, amplified by commentary from Jimmy Dore on The Jimmy Dore Show, suggests that Epstein previously underwent a radical prostatectomy — a complete removal of the prostate gland — yet autopsy notes reportedly reference the presence of a prostate. If true, proponents argue, the body examined could not have been Epstein’s.

“No way that was Jeffrey Epstein’s body,” Dore said during a segment now circulating widely on Instagram.

The Medical Claim

According to the show, documents in the “Epstein files” reference a radical prostatectomy performed on Epstein. Dore then cites what he describes as autopsy findings that mention a prostate being present and slightly enlarged.

The argument follows a simple line of reasoning: If Epstein’s prostate was surgically removed, and a prostate was observed during autopsy, then the body examined was not his.

The show further asserts that modern medicine cannot regenerate a fully functional human prostate, reinforcing the claim that such a discrepancy would be biologically impossible.

On its face, the logic appears straightforward — and for audiences already skeptical about the circumstances of Epstein’s 2019 death in federal custody, it lands as “almost conclusive proof,” as Dore phrased it.

Why Doubts Persist

Epstein’s death at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York was officially ruled a suicide by hanging. However, from the outset, the case has been dogged by irregularities: malfunctioning cameras, sleeping guards, and delayed checks.

Previous reporting, including coverage by ABC News, has detailed statements from Epstein’s brother and legal team questioning whether he took his own life.

The combination of high-profile associates, institutional failures, and sealed investigative records has kept conspiracy theories alive for years.

Examining the “Prostate Discrepancy”

But does the new claim withstand scrutiny?

Medical and forensic experts note that documentation terminology can be misunderstood by non-specialists. A radical prostatectomy removes the prostate gland, but surrounding tissue structures remain. In some cases, residual tissue or documentation shorthand may reference anatomical areas even after surgical removal.

Autopsy reports can also describe the region where an organ would be located, even if partially or fully absent. Without access to the complete medical file, including surgical records and full autopsy documentation, isolated excerpts can be misleading.

There is also no verified public confirmation — through court records or authenticated medical files — that Epstein underwent a radical prostatectomy.

As with many viral claims, the theory relies heavily on selective interpretation of documents whose provenance and context remain unclear.

The Pattern of Post-Death Conspiracies

High-profile deaths — especially those tied to powerful networks — frequently generate alternative narratives. In Epstein’s case, distrust of institutions fuels the persistence of such claims.

The unresolved public appetite for accountability in the broader Epstein scandal has created fertile ground for speculation. Many Americans remain dissatisfied with the scope of prosecutions connected to his case.

Yet suspicion alone does not constitute proof.

A Grand Cover-Up — Or a Grand Assumption?

The new prostate-based theory is persuasive to those already convinced that Epstein’s death was staged. But without independently verified medical records demonstrating both a confirmed prostatectomy and an authenticated autopsy contradiction, the argument remains speculative.

That does not erase the legitimate concerns surrounding how Epstein died under federal supervision. It does, however, underscore the importance of distinguishing between institutional failure and evidentiary proof of a body swap or staged death.

For now, the claim adds another chapter to one of the most controversial custodial deaths in modern American history — but not definitive closure.

In cases like this, the truth may not be simple. But it is rarely established through social media fragments alone.

Commentary

At a glance: US‑Israel attack on Iran

Digital Storytelling Team, The Conversation

The US and Israel have launched joint coordinated attacks on Iran, prompting retaliatory strikes from Iran on Israel and US military bases in the region.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader for 36 years, has been killed in the strikes, Iranian state media reported.

Iran’s Supreme National Security Council says he was killed early Saturday morning at his office. Satellite imagery shows significant damage to parts of the Leadership House compound, which is Khamenei’s office in Tehran.

Iranian school struck

More than 100 children have reportedly been killed by US and Israeli air strikes on a school, according to Iranian authorities. They say the strikes hit a girls’ elementary school in the city of Minab in the country’s south.

Video has emerged of crowds of people searching through the rubble.

“Hundreds of civilians have been killed and injured as a result of the aggression and atrocious crime of the United States regime and the Israeli regime, and the deliberate … targeting of civilian infrastructure,” Amir-Saeid Iravani, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, told an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council.

Digital Storytelling Team, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Opinion

What the Exchange Rate Conceals: Ghana’s hidden cost of living crisis

While Ghana’s headline macroeconomic indicators—falling inflation, a sharply appreciating cedi, and IMF programme progress—have earned international praise, a deeper, quieter crisis continues to erode the daily lives of ordinary citizens, writes Dominic Senayah. In this powerful opinion piece, the policy analyst and international relations professional argues that the country’s recent exchange-rate stability masks a structural cost-of-living emergency that no salary can reasonably sustain.

What the Exchange Rate Conceals: Ghana’s hidden cost of living crisis

By Dominic Senayah

There is a quiet arithmetic to suffering. It does not make front pages. It does not generate dramatic headlines that bring in international cameras or set Parliament alight. It happens instead at the market stall, at the landlord’s door, at the end of the month when the salary notification arrives, and the mental calculation begins and fails. It is the arithmetic of a country where the cost of simply existing has outpaced the means by which ordinary people are expected to exist. This is Ghana’s hidden cost of living crisis, and those of us who love the country, who hold its passport, who carry it with us wherever we go in the world, can no longer afford to normalise it.

I write this as a Ghanaian living and working in England. The distance has not made me detached. If anything, the contrast has sharpened my concern. I know what a functioning relationship between wages, housing, and food looks like in practice. And I know that what Ghana has at present falls far short of what it is capable of delivering to its people.

The Rent That No Salary Can Justify

Let us begin where every life begins, with a roof. As of early 2026, a one-bedroom apartment in Accra commands around GH₵2,200 per month, with Cantonments, Airport Residential, and Labone pushing considerably higher. But the monthly rate is only part of the punishment. It is normal in Ghana to pay one or two years of rent upfront, placing an enormous financial demand on a tenant before they have even moved in. The average monthly salary sits at approximately GH₵2,579 — roughly $210 at current exchange rates — with entry-level civil servants earning between GH₵2,200 and GH₵3,200. A mid-level public servant asked to pay two years upfront on a modest Accra flat faces a demand exceeding a full year of gross salary, payable before a single sock has been unpacked.

The comparison with Nigeria is instructive. Lagos — Africa’s most commercially intense city, far larger and more complex than Accra, regularly offers comparable housing at lower dollar-equivalent rates. That a smaller city prices its residents more aggressively is a structural anomaly deserving frank scrutiny. Ghana’s landlord class, hedging against cedi depreciation through dollar-denominated rents, has turned housing into a mechanism of extraction that the wage economy cannot support. The result is a generation of professionals commuting three to five hours daily because they cannot afford to live near where they work.

A Country That Grows Food and Cannot Afford to Feed Itself

Ghana spans multiple agro-ecological zones supporting cocoa, yams, plantains, cassava, tomatoes, pepper, groundnuts, maize, and rice. The ecological potential is profound. And yet the price of tomatoes in an Accra market routinely exceeds what the same produce costs in countries that must import it from thousands of miles away. This is a policy failure, not a natural one. According to the World Food Programme, Ghana loses US$1.9 billion annually to post-harvest waste due to poor road networks, inadequate storage, and the near-total absence of cold chain infrastructure, with losses estimated between 20 and 50 per cent across various crop types. The farmer in Brong-Ahafo who watches tomatoes rot on the roadside because the truck did not come is not a lazy farmer. He is a farmer abandoned by systems never built with sufficient urgency.

At the consumer end, supply is erratic, middlemen extract margins at every link, and what arrives in the city comes bruised and expensive. Ghana, once a significant tomato producer in West Africa, now imports over 7,000 metric tons of tomatoes annually from neighbouring countries. The same logic applies to rice, poultry, and a growing range of processed foods. Ghana has fertile land and an empty value chain, and until the infrastructure connecting the two is treated as a national emergency, this contradiction will persist.

Salaries, Corruption, and the Structural Explanation Nobody Wants to Give

Petty corruption in Ghana is routinely framed as a moral failure. The condemnation is not unwarranted, but it rarely arrives at the structural diagnosis necessary for real solutions. When a port official takes an unofficial payment or a nurse charges informally for a service that should be free, the issue is often not characterised. It is mathematics. If the average salary is GH₵2,579 and a basic one-bedroom flat in Accra costs between GH₵1,500 and GH₵2,800 per month, the gap between income and shelter is insurmountable before a single meal or school fee is considered. People in structurally impossible positions find structural workarounds. Ghana cannot build trustworthy institutions on the foundation of a workforce that cannot survive on its formal income. The enforcement agencies expected to police corruption while living within these same constraints are being asked to do something human societies have always found very difficult to sustain.

The Import Economy’s Double Standard

Walk through any Ghanaian market, and the shelves are full of Chinese electronics with dubious longevity, imported cooking oil, and imported clothing. The quality differential between goods manufactured for African markets and those produced by the same factories for Western consumers is not accidental. It is a calibrated response to weak regulatory environments. Where consumer protection law lacks enforcement, the incentive to produce durably disappears. Ghanaian consumers are being sold shorter lifespans in their goods and longer suffering in their wallets. Capital that could fund agro-processing in the forest belt or cold chain infrastructure in the north instead cycles through import speculation with a six-month horizon, extracting from the population rather than building it up.

Towards Price Regulation: What Is Actually Feasible

This is where most commentary on Ghana’s cost of living crisis falls short, diagnosing the problem without engaging seriously with solutions. Full command-style price fixing is not the answer. Ghana tried broad price controls under the Rawlings era, and the outcome was predictable: market distortions, shortages, and a thriving black market that harmed the very people it was meant to protect. But there is a meaningful space between laissez-faire chaos and discredited command economies, and Ghana has both the institutional architecture and the precedent from comparable economies to occupy it.

The first viable intervention is a national reference pricing system for staple goods. The government already publishes some commodity price data, but inconsistently and with almost no reach into the market itself. A properly resourced weekly publication of government-verified benchmark prices for staple foods displayed at market entrances, bus terminals, and broadcast via radio and SMS to rural communities arms the consumer with information, which is the most powerful and least distorting check on seller greed. Rwanda has implemented this model for agricultural produce with a measurable effect on price gouging at the retail level. It preserves market freedom while eliminating the information asymmetry that predatory pricing depends upon.

The second is a functioning rent tribunal. Ghana’s Rent Act of 1963 technically prohibits excessive advance payment demands, but it is widely ignored because the mechanism for enforcing it is inaccessible to ordinary tenants. A simplified housing tribunal modelled on those that operate effectively in South Africa and the United Kingdom, that allows tenants to challenge dollar-denominated rents and multi-year upfront demands, would be a targeted, enforceable intervention requiring legislative update rather than significant fiscal outlay. The legal framework exists. What is missing is the political will to resource and publicise it.

The third is deeper utilisation of the Ghana Commodity Exchange, launched in 2018 but still dramatically underused. A functioning commodity exchange creates transparent, publicly visible price discovery for agricultural goods, which structurally reduces the power of middlemen to arbitrarily inflate margins between farm gate and urban market. Integrating smallholder farmers and market women through mobile phone access is both technically feasible and commercially attractive given Ghana’s mobile penetration rates. This is not a distant aspiration. It is an operational gap in an existing institution.

The fourth is consumer protection enforcement with genuine deterrent value. Current fines under the Consumer Protection Agency Act are derisory relative to the profits available from price exploitation. Raising penalty thresholds meaningfully and giving the agency a publicised rapid-response function, a hotline that triggers market inspection within 48 hours of a complaint,t would shift the risk calculus for sellers without requiring price fixing of any kind. None of these measures alone resolves the crisis. Together, they constitute a coherent, Ghana-feasible regulatory architecture that addresses greed at its structural root rather than its moral surface.

Where the Government Has Done Well — And What Must Follow

Macroeconomic honesty requires acknowledging what has been achieved. Inflation fell for thirteen consecutive months, from 23.5 per cent in January 2025 to 3.8 per cent in January 2026, single digits for the first time since 2021. The cedi appreciated 40.7 per cent against the dollar in 2025, reversing the prior year’s 19.2 per cent depreciation, earning World Bank recognition as the best-performing currency in Sub-Saharan Africa. The IMF completed its fifth Extended Credit Facility review in December 2025 with positive assessments across growth, reserves, and debt trajectory. Currency stability anchors import prices, reduces the landlord’s dollar-denomination incentive, and creates the predictability businesses need. But stability is the floor of a better economy, not its ceiling. The ceiling requires structural transformation in agriculture, manufacturing, institutional quality, and the wage-to-cost relationship,p which stabilisation enables but cannot itself deliver.

The Reorientation Ghana Needs

Ghana will not become Denmark overnight, and no reasonable person expects that. But the distance between where Ghana is and where it is capable of being is not as vast as learned helplessness suggests. Wealthy Ghanaians must be persistently encouraged, through deliberate policy incentives andcultural expectationsn, to invest in domestic productive capacity rather than import speculation or offshore accumulation. Patient capital that builds agro-processing, cold chain networks, or quality housing is less glamorous than a Shenzhen container but far more durable as national wealth.

Young Ghanaians expressing frustration are not being ungrateful. They are giving accurate feedback to a system that has not yet decided to work for them. Their constrained futures are not the inevitable consequence of poverty but the outcome of choices about investment, infrastructure, and the relationship between wages and the cost of living that can be made differently.

The exchange rate is the number the world watches closely. What it conceals is the daily life Ghanaians actually live. The stability of 2025 has been earned. Now comes the harder, more human work of making it mean something to the nurse in Tamale, the graduate in Kumasi, and the family in Nima who still cannot make the numbers add up.

About the Author

Dominic Senayah is an International Relations professional and policy analyst based in England, specialising in African political economy, humanitarian governance, and migration diplomacy. He holds an MA in International Relations from the UK and writes on trade policy, institutional reform, and Ghana–UK relations for audiences across Africa, the United Kingdom, and the wider Global South.

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoGhana Gears Up for Vibrant 69th Independence Day Celebrations: Parades, Plays, Poetry, and Heritage in Focus

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoNewspaper Headlines Today: Tuesday, March 3, 2026

-

Tourism2 days ago

Tourism2 days agoEmirates Resumes Limited Flights from Dubai as Middle East Airspace Slowly Reopens Amid Ongoing Conflict

-

Commentary2 days ago

Commentary2 days agoAt a glance: US‑Israel attack on Iran

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoAyawaso East By-Election Results Trickle in, ECG Audits Fast-Reading Meters, and Other Trending Topics in Ghana (March 3, 2026)

-

Ghana News1 day ago

Ghana News1 day agoGhana’s Top Muslim Leader Condemns Khamenei Assassination, Calls for New World Order Based on ‘Right Over Might’

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoGhana’s Mega Infrastructure Push: 10 Game-Changing Projects Set to Transform the Country in 2026

-

Fashion & Style1 day ago

Fashion & Style1 day agoThe New Wave of “Afro-Minimalism”: Redefining Luxury Beyond the Print