Opinion

Ghana’s Democracy at Risk: When institutions trade conscience for interest

Human rights advocate, Isaac Ofori, surmises in this opinion piece that Ghana’s democracy, often hailed as maturing, is increasingly threatened by the erosion of institutional integrity, where civil society organizations, media, faith-based groups, and universities prioritize political loyalty and self-interest over accountability and public service.

—————————

Ghana’s democracy is often described as maturing.

Yet, this maturity is increasingly disconnected from the everyday realities of citizens.

What has emerged is a cyclical democratic order that appears to serve a narrow political class and its affiliates rather than advancing a shared national vision of development, equity, and integrity.

For many Ghanaians, the promise of a society grounded in accountability and free from corruption remains distant.

The two dominant political parties of the Fourth Republic have perfected the art of justifying misconduct while in office.

At the same time, opposition politics has been reduced mainly to one objective: regaining power.

The more profound concern, however, lies beyond these parties. It rests with the institutions that ought to restrain them.

Civil society organisations, once central to democratic accountability, have seen their credibility steadily erode.

Many individuals who claim neutrality are, in practice, deeply embedded partisan actors.

CSOs that should provide independent oversight and advocate for good governance have increasingly functioned as extensions of political machinery.

Their public posture often shifts depending on which party they align with, and some have gone so far as to openly defend governments even in moments of apparent failure.

The result is a weakened system of checks and balances, in which institutional vigilance is compromised by political loyalty and personal ambition.

The media, too, has drifted from its constitutional role as the fourth estate. Rather than serving as a fearless watchdog, much of the media landscape has become entangled in partisan interests.

Prominent journalists now rely on political patronage, and media ownership is closely tied to political power.

This alignment has hollowed out the media’s moral authority.

Instead of interrogating power, media platforms increasingly defend the ruling government or amplify opposition narratives.

The ordinary Ghanaian is left without an independent voice, watching as truth is filtered through fear, convenience, or financial gain.

Other influential bodies have not been spared.

The Christian Council of Ghana, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference, and similar civic or faith-based organisations appear to have lost their moral voice in national discourse.

Whether through overt politicisation or quiet self-interest, their engagement in governance has weakened.

Ghana’s universities and higher institutions, which should be engines of critical thought and public reasoning, have similarly fallen short.

Academic voices are muted, often constrained by political alignment or institutional caution, leaving national debates impoverished of evidence-based critique.

At the core of this democratic erosion is unchecked self-interest.

The recent GOLDBOD controversy, involving losses exceeding $200 million, is not merely a financial scandal.

It is a stark illustration of institutional decay.

It reveals how weakened democratic actors have become and how easily political leaders can rationalise grave missteps under the guise of national interest.

The issue is not only the loss itself but what it represents: a democracy suffocated by selective silence, convenient justifications, and competing interests focused on survival rather than national progress.

This moment demands urgent reflection.

Ghana’s democracy is not failing because of elections or constitutional form, but because the institutions meant to protect it have traded principle for proximity to power.

Without a deliberate recommitment to independence, integrity, and public accountability, democratic maturity will remain an illusion, and its cost will continue to be borne by the very citizens it was meant to serve.

The author, Isaac Ofori, is a Social Activist and Human Rights Advocate

Opinion

What the Exchange Rate Conceals: Ghana’s hidden cost of living crisis

While Ghana’s headline macroeconomic indicators—falling inflation, a sharply appreciating cedi, and IMF programme progress—have earned international praise, a deeper, quieter crisis continues to erode the daily lives of ordinary citizens, writes Dominic Senayah. In this powerful opinion piece, the policy analyst and international relations professional argues that the country’s recent exchange-rate stability masks a structural cost-of-living emergency that no salary can reasonably sustain.

What the Exchange Rate Conceals: Ghana’s hidden cost of living crisis

By Dominic Senayah

There is a quiet arithmetic to suffering. It does not make front pages. It does not generate dramatic headlines that bring in international cameras or set Parliament alight. It happens instead at the market stall, at the landlord’s door, at the end of the month when the salary notification arrives, and the mental calculation begins and fails. It is the arithmetic of a country where the cost of simply existing has outpaced the means by which ordinary people are expected to exist. This is Ghana’s hidden cost of living crisis, and those of us who love the country, who hold its passport, who carry it with us wherever we go in the world, can no longer afford to normalise it.

I write this as a Ghanaian living and working in England. The distance has not made me detached. If anything, the contrast has sharpened my concern. I know what a functioning relationship between wages, housing, and food looks like in practice. And I know that what Ghana has at present falls far short of what it is capable of delivering to its people.

The Rent That No Salary Can Justify

Let us begin where every life begins, with a roof. As of early 2026, a one-bedroom apartment in Accra commands around GH₵2,200 per month, with Cantonments, Airport Residential, and Labone pushing considerably higher. But the monthly rate is only part of the punishment. It is normal in Ghana to pay one or two years of rent upfront, placing an enormous financial demand on a tenant before they have even moved in. The average monthly salary sits at approximately GH₵2,579 — roughly $210 at current exchange rates — with entry-level civil servants earning between GH₵2,200 and GH₵3,200. A mid-level public servant asked to pay two years upfront on a modest Accra flat faces a demand exceeding a full year of gross salary, payable before a single sock has been unpacked.

The comparison with Nigeria is instructive. Lagos — Africa’s most commercially intense city, far larger and more complex than Accra, regularly offers comparable housing at lower dollar-equivalent rates. That a smaller city prices its residents more aggressively is a structural anomaly deserving frank scrutiny. Ghana’s landlord class, hedging against cedi depreciation through dollar-denominated rents, has turned housing into a mechanism of extraction that the wage economy cannot support. The result is a generation of professionals commuting three to five hours daily because they cannot afford to live near where they work.

A Country That Grows Food and Cannot Afford to Feed Itself

Ghana spans multiple agro-ecological zones supporting cocoa, yams, plantains, cassava, tomatoes, pepper, groundnuts, maize, and rice. The ecological potential is profound. And yet the price of tomatoes in an Accra market routinely exceeds what the same produce costs in countries that must import it from thousands of miles away. This is a policy failure, not a natural one. According to the World Food Programme, Ghana loses US$1.9 billion annually to post-harvest waste due to poor road networks, inadequate storage, and the near-total absence of cold chain infrastructure, with losses estimated between 20 and 50 per cent across various crop types. The farmer in Brong-Ahafo who watches tomatoes rot on the roadside because the truck did not come is not a lazy farmer. He is a farmer abandoned by systems never built with sufficient urgency.

At the consumer end, supply is erratic, middlemen extract margins at every link, and what arrives in the city comes bruised and expensive. Ghana, once a significant tomato producer in West Africa, now imports over 7,000 metric tons of tomatoes annually from neighbouring countries. The same logic applies to rice, poultry, and a growing range of processed foods. Ghana has fertile land and an empty value chain, and until the infrastructure connecting the two is treated as a national emergency, this contradiction will persist.

Salaries, Corruption, and the Structural Explanation Nobody Wants to Give

Petty corruption in Ghana is routinely framed as a moral failure. The condemnation is not unwarranted, but it rarely arrives at the structural diagnosis necessary for real solutions. When a port official takes an unofficial payment or a nurse charges informally for a service that should be free, the issue is often not characterised. It is mathematics. If the average salary is GH₵2,579 and a basic one-bedroom flat in Accra costs between GH₵1,500 and GH₵2,800 per month, the gap between income and shelter is insurmountable before a single meal or school fee is considered. People in structurally impossible positions find structural workarounds. Ghana cannot build trustworthy institutions on the foundation of a workforce that cannot survive on its formal income. The enforcement agencies expected to police corruption while living within these same constraints are being asked to do something human societies have always found very difficult to sustain.

The Import Economy’s Double Standard

Walk through any Ghanaian market, and the shelves are full of Chinese electronics with dubious longevity, imported cooking oil, and imported clothing. The quality differential between goods manufactured for African markets and those produced by the same factories for Western consumers is not accidental. It is a calibrated response to weak regulatory environments. Where consumer protection law lacks enforcement, the incentive to produce durably disappears. Ghanaian consumers are being sold shorter lifespans in their goods and longer suffering in their wallets. Capital that could fund agro-processing in the forest belt or cold chain infrastructure in the north instead cycles through import speculation with a six-month horizon, extracting from the population rather than building it up.

Towards Price Regulation: What Is Actually Feasible

This is where most commentary on Ghana’s cost of living crisis falls short, diagnosing the problem without engaging seriously with solutions. Full command-style price fixing is not the answer. Ghana tried broad price controls under the Rawlings era, and the outcome was predictable: market distortions, shortages, and a thriving black market that harmed the very people it was meant to protect. But there is a meaningful space between laissez-faire chaos and discredited command economies, and Ghana has both the institutional architecture and the precedent from comparable economies to occupy it.

The first viable intervention is a national reference pricing system for staple goods. The government already publishes some commodity price data, but inconsistently and with almost no reach into the market itself. A properly resourced weekly publication of government-verified benchmark prices for staple foods displayed at market entrances, bus terminals, and broadcast via radio and SMS to rural communities arms the consumer with information, which is the most powerful and least distorting check on seller greed. Rwanda has implemented this model for agricultural produce with a measurable effect on price gouging at the retail level. It preserves market freedom while eliminating the information asymmetry that predatory pricing depends upon.

The second is a functioning rent tribunal. Ghana’s Rent Act of 1963 technically prohibits excessive advance payment demands, but it is widely ignored because the mechanism for enforcing it is inaccessible to ordinary tenants. A simplified housing tribunal modelled on those that operate effectively in South Africa and the United Kingdom, that allows tenants to challenge dollar-denominated rents and multi-year upfront demands, would be a targeted, enforceable intervention requiring legislative update rather than significant fiscal outlay. The legal framework exists. What is missing is the political will to resource and publicise it.

The third is deeper utilisation of the Ghana Commodity Exchange, launched in 2018 but still dramatically underused. A functioning commodity exchange creates transparent, publicly visible price discovery for agricultural goods, which structurally reduces the power of middlemen to arbitrarily inflate margins between farm gate and urban market. Integrating smallholder farmers and market women through mobile phone access is both technically feasible and commercially attractive given Ghana’s mobile penetration rates. This is not a distant aspiration. It is an operational gap in an existing institution.

The fourth is consumer protection enforcement with genuine deterrent value. Current fines under the Consumer Protection Agency Act are derisory relative to the profits available from price exploitation. Raising penalty thresholds meaningfully and giving the agency a publicised rapid-response function, a hotline that triggers market inspection within 48 hours of a complaint,t would shift the risk calculus for sellers without requiring price fixing of any kind. None of these measures alone resolves the crisis. Together, they constitute a coherent, Ghana-feasible regulatory architecture that addresses greed at its structural root rather than its moral surface.

Where the Government Has Done Well — And What Must Follow

Macroeconomic honesty requires acknowledging what has been achieved. Inflation fell for thirteen consecutive months, from 23.5 per cent in January 2025 to 3.8 per cent in January 2026, single digits for the first time since 2021. The cedi appreciated 40.7 per cent against the dollar in 2025, reversing the prior year’s 19.2 per cent depreciation, earning World Bank recognition as the best-performing currency in Sub-Saharan Africa. The IMF completed its fifth Extended Credit Facility review in December 2025 with positive assessments across growth, reserves, and debt trajectory. Currency stability anchors import prices, reduces the landlord’s dollar-denomination incentive, and creates the predictability businesses need. But stability is the floor of a better economy, not its ceiling. The ceiling requires structural transformation in agriculture, manufacturing, institutional quality, and the wage-to-cost relationship,p which stabilisation enables but cannot itself deliver.

The Reorientation Ghana Needs

Ghana will not become Denmark overnight, and no reasonable person expects that. But the distance between where Ghana is and where it is capable of being is not as vast as learned helplessness suggests. Wealthy Ghanaians must be persistently encouraged, through deliberate policy incentives andcultural expectationsn, to invest in domestic productive capacity rather than import speculation or offshore accumulation. Patient capital that builds agro-processing, cold chain networks, or quality housing is less glamorous than a Shenzhen container but far more durable as national wealth.

Young Ghanaians expressing frustration are not being ungrateful. They are giving accurate feedback to a system that has not yet decided to work for them. Their constrained futures are not the inevitable consequence of poverty but the outcome of choices about investment, infrastructure, and the relationship between wages and the cost of living that can be made differently.

The exchange rate is the number the world watches closely. What it conceals is the daily life Ghanaians actually live. The stability of 2025 has been earned. Now comes the harder, more human work of making it mean something to the nurse in Tamale, the graduate in Kumasi, and the family in Nima who still cannot make the numbers add up.

About the Author

Dominic Senayah is an International Relations professional and policy analyst based in England, specialising in African political economy, humanitarian governance, and migration diplomacy. He holds an MA in International Relations from the UK and writes on trade policy, institutional reform, and Ghana–UK relations for audiences across Africa, the United Kingdom, and the wider Global South.

Opinion

Resetting Sovereignty: Mahama’s Foreign Policy and the Constitutional Revival of NKRUMAHISM 60 years after the 1966 Coup

This opinion piece by Victoria Hamah (PhD) argues that President John Dramani Mahama’s foreign-policy direction reflects a renewed commitment to Kwame Nkrumah’s ideas of sovereignty, non-alignment, and economic independence. It points to symbolic actions—such as renaming Kotoka International Airport back to Accra International Airport—as part of a broader effort to correct historical narratives, strengthen national autonomy, and revive a modern, constitutional form of Nkrumahism 60 years after the 1966 coup.

Resetting Sovereignty: Mahama’s Foreign Policy and the Constitutional Revival of NKRUMAHISM 60 years after the 1966 Coup

After 60 years, the most shameful blot on the page of national dignity has finally been erased. The Kotoka International Airport has been reverted to its rightful name, Accra International Airport.

This decision by President John Mahama represents more than just an administrative rebranding. It signals an effort to interrogate the historical foundations upon which the postcolonial Ghanaian state was constructed.

The airport was named after Lieutenant General Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka, a central figure in the 1966 coup which overthrew Kwame Nkrumah. That coup marked a decisive interruption of Ghana’s early post-independence developmental trajectory and inaugurated a period of political instability, throwing Ghana, then the lodestar of Africa, into the decadence of neocolonial subjugation.

Recently declassified records from the Central Intelligence Agency have confirmed that the United States, Britain and France were actively involved in the planning of the coup. While debates persist regarding the precise degree of foreign involvement, the broader historical consensus recognises that the overthrow of Nkrumah occurred within a broader context of Western imperialist efforts to derail the independent developmental model in particular and the pan-African vision in general.

Within this frame, the renaming of the airport functions as an act of narrative correction. It does not merely revisit the legacy of one military officer who was nothing more than a soldier of fortune; it symbolically re-centres Ghana’s identity around civilian constitutional sovereignty rather than military intervention.

In doing so, it aligns with the broader philosophical thrust of President Mahama: that political and economic independence must be reclaimed not only through fiscal and industrial policy, but through the stories nations tell about their own past.

This symbolic gesture addresses an earlier rupture in Ghana’s sovereign development. Together, they articulate a consistent thesis: that independence is neither a completed event nor a ceremonial inheritance, but an ongoing political project requiring institutional, economic, and historical recalibration.

The symbolic timing is equally significant. Sixty years after the infamous 24th February 1966 coup d’état, the renaming signals more than historical reconsideration; it suggests an ideological repositioning.

It indicates an aspiration by the National Democratic Congress (NDC) government toward a consciously pro-Nkrumahist orientation, one grounded in non-alignment, strategic autonomy, and policy independence amid an increasingly turbulent global order.

For John Dramani Mahama’s administration, this does not imply a retreat into isolationism nor a rejection of global engagement. Rather, it reflects a recalibration of Ghana’s external posture: cooperation without subordination, partnership without policy capture.

In a period marked by intensifying geopolitical rivalry and assertive economic diplomacy from powerful states in the Global North, particularly Western nations. The gesture evokes the earlier doctrine of Kwame Nkrumah, who situated Ghana within the Non-Aligned Movement as a sovereign actor rather than a peripheral client.

Read in this light, the act is not revisionist symbolism for its own sake. It articulates a continuity between the Accra Reset and Ghana’s unfinished post-independence project. The 1966 coup interrupted an ambitious experiment in autonomous development and continental leadership.

To revisit that rupture six decades later is to suggest that the questions posed in the 1960s -abhorrent alignment, dependency, and the boundaries of sovereignty – should define the character of political debate.

Economic Sovereignty as a Foreign Policy: The Reset in Practice:

President John Dramani Mahama’s unprecedented post-Rawlings era electoral victory carries significance beyond partisan transition. It represents, symbolically, a renaissance of Nkrumahism within Ghana’s contemporary democratic framework.

For the first time since the revolutionary and post-revolutionary dominance of Jerry Rawlings, a renewed mandate has been secured on a platform explicitly invoking structural transformation, strategic autonomy, and continental alignment rather than mere macroeconomic stabilisation.

This moment also clarifies an older historical debate. Prior to the 24 February 1966 coup that overthrew Kwame Nkrumah, there were persistent allegations, advanced by Nkrumah himself, that Western powers, uneasy with Ghana’s non-aligned posture and pan-African activism, exerted economic pressure by manipulating global cocoa markets.

As cocoa was Ghana’s principal export and foreign exchange earner, its price volatility had profound fiscal implications. Some historical interpretations further suggest tacit alignment by neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire, which is also a major cocoa producer within broader Western-aligned commodity structures, thereby compounding Ghana’s vulnerability and creating the mood for violent regime change.

Whether interpreted as deliberate sabotage or structural dependency within a commodity-based global economy, the episode reinforced a central Nkrumahist lesson: political sovereignty without economic autonomy is fragile.

Mahama’s present mandate appears framed as an effort to transcend that vulnerability without repudiating constitutional democracy or global engagement.

A key example is the decision to move away from syndicated external financing arrangements in the cocoa sector and to prioritise domestic value addition by processing up to half of Ghana’s cocoa output locally. This signals a deliberate shift from dependence on raw commodities toward industrial upgrading.

If implemented effectively, this approach aligns closely with classical Nkrumahist economic thought: retaining greater value within the domestic economy, reducing exposure to external price shocks, and building industrial capacity anchored in existing comparative advantage. It is not autarky but strategic repositioning within global markets.

Describing this moment as a renaissance of Nkrumahism, therefore, does not imply a return to one-party statism or Cold War binaries. Rather, it signals the re-emergence of core principles of economic self-determination, continental integration, and calibrated non-alignment within a competitive multiparty order.

Taken together, the symbolic reconsideration of colonial-era commemorations, the Nkrumahist articulation of foreign policy by Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa, reforms within the cocoa financing architecture, and Mahama’s renewed electoral mandate, the moment can be read as deliberate ideological consolidation. It suggests that the questions suspended in 1966 have re-entered Ghana’s political centre, not as nostalgia, but as a strategy: a constitutionalised revival of the unfinished project of autonomous development.

Thus, the Reset Agenda operates on three registers simultaneously: economic restructuring, institutional reform, and historical re-anchoring. Together, they imply that sovereignty is not merely territorial integrity nor formal democratic procedure, but the sustained capacity to determine national priorities without external veto.

If the coup marked the suspension of that ambition, the present moment is framed as its cautious revival.

Opinion

Staying the Course of Ethical Journalism in an Era of Misinformation and AI

In this opinion piece, experienced journalist Kizito Cudjoe urges Ghanaian media to uphold ethical standards amid rising misinformation and AI tools. While technology aids reporting, rushed event-driven coverage and lack of verification erode public trust. He advocates reaffirming verification, balance, and integrity—using AI as an assistant, not a replacement—for journalism to maintain relevance and credibility.

Staying the Course of Ethical Journalism in an Era of Misinformation and AI

By Kizito Cudjoe

Journalism, at its best, is anchored in professionalism, a passion to inform and educate, and an unrelenting commitment to the public good. These principles have guided the craft for generations. Yet today, amid the rapid rise of digital technology and artificial intelligence, the profession faces a new and serious test.

Technology was meant to strengthen journalism. Properly used, it allows reporters to gather data faster, verify facts more thoroughly, and reach wider audiences.

But tools can also be misused.

In recent years, the ease with which content can be generated, especially with AI systems, has lowered the barrier to entry in ways that sometimes erode standards. Anyone can now produce something that looks like a news story, but not everyone practices journalism.

After more than 14 years working both locally and beyond our borders, one pattern continues to concern me. Here in Ghana, much of our reporting remains heavily event-driven, and too often facts are reproduced without rigorous questioning or verification. The pressure to be first has replaced the duty to be right. This culture risks weakening public trust in the media.

When stories are rushed without scrutiny, misinformation spreads easily. Worse, it reinforces the perception among professionals in other fields that journalists are merely conduits for press releases or talking points. That perception is unfair to many hardworking reporters, but it grows each time unverified information reaches the public.

The answer is not to reject technology or fear AI. It is to reaffirm the discipline that defines our craft. Verification, balance, context, and accountability must remain non-negotiable. Every newsroom, regardless of size or editorial style, should insist on basic checks and balances before publication, not only to protect the public from falsehoods, but also to protect journalists themselves from reputational and legal harm.

Artificial intelligence can assist with research, transcription, and analysis. It cannot replace judgement, integrity, or experience. Those qualities still define professional journalism. Tools may evolve, but ethics must endure.

If journalism in this country is to retain its relevance and respect, we must recommit to those principles.

The future of the profession will not be decided by technology alone, but by the standards we choose to uphold.

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoGhana Gears Up for Vibrant 69th Independence Day Celebrations: Parades, Plays, Poetry, and Heritage in Focus

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoNewspaper Headlines Today: Tuesday, March 3, 2026

-

Tourism2 days ago

Tourism2 days agoEmirates Resumes Limited Flights from Dubai as Middle East Airspace Slowly Reopens Amid Ongoing Conflict

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoAyawaso East By-Election Results Trickle in, ECG Audits Fast-Reading Meters, and Other Trending Topics in Ghana (March 3, 2026)

-

Commentary2 days ago

Commentary2 days agoAt a glance: US‑Israel attack on Iran

-

Ghana News2 days ago

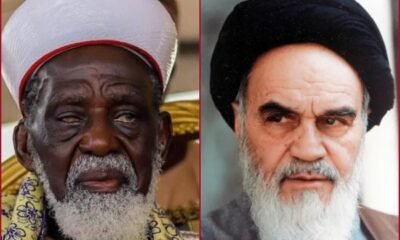

Ghana News2 days agoGhana’s Top Muslim Leader Condemns Khamenei Assassination, Calls for New World Order Based on ‘Right Over Might’

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoGhana’s Mega Infrastructure Push: 10 Game-Changing Projects Set to Transform the Country in 2026

-

Fashion & Style2 days ago

Fashion & Style2 days agoThe New Wave of “Afro-Minimalism”: Redefining Luxury Beyond the Print