Editorial

Editorial: Anthony Joshua’s Lagos Crash Is An Urgent Call for Stronger Emergency Response Systems Across Africa

The harrowing car accident involving British boxing champion Anthony Joshua on Nigeria’s Lagos–Ibadan Expressway was deeply painful, not just for the loss of life, but for what the incident reveals about public safety and emergency response capabilities that affect ordinary citizens every day.

On December 29, 2025, Joshua was involved in a serious road collision near Makun, Ogun State, when the SUV he was traveling in struck a stationary truck. Two of his close associates — strength and conditioning coach Sina Ghami and trainer Latif “Latz” Ayodele — were killed. Joshua himself escaped with minor injuries and was discharged from a Lagos hospital on January 1, 2026.

While the boxer’s survival and medical clearance are encouraging, the footage and accounts circulating online from the scene have drawn fierce criticism for the apparent absence of organized emergency medical care.

Videos showed onlookers gathered at the crash site, the bodies of the deceased left on the road, and Joshua was eventually transported in a police vehicle rather than by prompt ambulance care.

Africa faces some of the highest road fatality rates in the world. Even before this accident, Nigeria alone recorded more than 5,400 road deaths in 2024 — an increase from the previous year. Yet the public response — or lack thereof — to a high-profile incident involving a globally recognized figure exposes broader systemic gaps in emergency preparedness and public health infrastructure.

There is no argument that quick and well-equipped emergency medical services (EMS) can be the difference between life and death in such crashes. Some analysts argue that, had professional emergency response teams arrived immediately and been fully equipped, there is a possibility the two victims could have survived initial trauma. This fact was the reason there was so much outrage in Nigeria and across the world following the fatal accident.

But the truth is, this incident of poor EMS isn’t unique to Nigeria. Across many African countries, EMS systems are chronically underfunded or unevenly distributed. Ambulance services, rapid trauma response teams, and integrated communication networks that automatically dispatch aid after accidents are often lacking, especially outside major urban centers. In contrast, many countries in Europe and North America have well-coordinated EMS protocols that routinely see ambulances and emergency personnel at accident scenes within minutes.

For diasporans — Africans living abroad who maintain deep cultural and emotional ties to their countries of origin — this episode should prompt honest reflection. It’s understandable to yearn for connection with the “motherland,” especially during festive seasons or career hiatuses. Africa’s vibrant cultures, rich history, and growing economies make it a powerful source of identity and opportunity. But that connection should be balanced with a clear-eyed understanding of local realities, especially regarding public services and safety infrastructures that directly affect health outcomes.

The reality is that emergency medical services are foundational to modern societies. They not only save lives but also foster public confidence in government competency and social stability. Effective EMS requires investment in training, equipment, emergency telecommunications, and public health policy — areas where many African governments have struggled to keep pace with rapid population growth and urbanization.

There are signs of progress. Some African countries are investing in EMS reform, public–private partnerships for trauma care, and community health worker initiatives that extend limited resources into broader networks of care. But the urgent need for systemic reforms remains. Ghana has a well-structured EMS regime; however, the lack of adequate equipment and personnel remains a stumbling block to world-standard functionality.

Diasporans and global partners who seek to engage with the continent — whether for investment, tourism, or family — should view this tragic incident as a call to advocate for stronger public health systems. Supporting initiatives that build robust emergency response frameworks isn’t just philanthropy; it is an investment in human capital and shared future prosperity.

While devastating, may Anthony Joshua’s crash wake up the continent invest in a global-standard emergency care service, one that is at par with the U.S. and Europe – the very places the African diasporans we are calling back home have lived all their lives.

Editorial

Renaming Kotoka International Airport: Let’s Honor Nkrumah and Complete Ghana’s Narrative

Ghana faces a defining moment. The proposal to rename Kotoka International Airport has once again ignited passionate debates.

On one side, proponents see it as a vital step toward purging symbols of coups and instability, arguing that honoring Lieutenant-General Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka—a key architect of the 1966 overthrow—undermines our democratic ethos. On the other, critics decry the move as needless revisionism, warning that it risks erasing complex historical layers and diverting attention from pressing economic woes. These contrasting views, while valid in highlighting the tension between progress and preservation, miss a deeper opportunity: any renaming effort that sidesteps Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah is not just shortsighted but fundamentally half-baked.

Ghana stands at a pivotal moment in its post-colonial journey, one where Nkrumah’s visionary ideals of pan-African unity, self-reliance, and continental renaissance are not relics of the past but blueprints for the future. Consider the “Year of Return” in 2019 and its extension into “Beyond the Return”—initiatives that have drawn thousands of African descendants back to our shores, fostering economic ties, cultural reconnection, and a renewed sense of African pride.

Nkrumah’s clarion call for a united Africa, free from neo-colonial shackles, resonates profoundly with this renaissance. His foresight in championing the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union) aligns seamlessly with today’s push for intra-African trade via the AfCFTA and the global reckoning with historical injustices like the transatlantic slave trade. Renaming the airport after Kotoka’s coup victim—Ghana’s founding president—would not merely correct a historical anomaly, it would signal to the world that Ghana is reclaiming its narrative in an era where African agency is ascendant.

There is no better symbolism for diasporan returnees arriving in Ghana — where their ancestors, centuries prior were sold into slavery — than arriving to reclaim their heritage at Kwame Nkrumah International Airport.

The reluctance to center Nkrumah exposes a national habit of incompleteness, a pattern etched into our landscape. Look no further than the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum in Accra: a grand tribute to the Osagyefo, yet one that feels unfinished. In fact, my reading on the design, which resembles a broken pyramid, is meant to reflect both Nkrumah’s unfinished Pan-African vision and Ghana’s continuing journey after him.

I am not an expert in symbols and symbolsim, but I feel deeply that that symbolism is self-defeating. Spiritually, it may suggest we will never get anything completed; we will always be in a perpetual cycle of starting things and never completing. I digress. Back to the airport renaming.

Renaming the airport “Kwame Nkrumah International Airport” would be a bold act of completion, transforming our gateway to the world into a monument of triumph rather than division. It would honor the man who built the original airfield as part of his ambitious development agenda, ensuring that every arriving visitor encounters Ghana through the lens of its liberator, not its disruptors. Sometimes, it feels like we are only ones (I mean Ghanaians) belittling Nkrumah’s influence and impact on the African continent. But if only we could throw away our political lenses, his grandeur and vision would be visible to all of us.

A bold decision like changing the name of a country’s main international airport demands careful consultation to avoid partisan pitfalls, but let’s not let fear of controversy perpetuate half-measures. Ghana deserves a symbol that inspires unity and ambition, not one mired in the dark shadows of 1966. Kotoka did Ghana no good by masterminding Nkrumah’s overthrow. Let’s not split hairs about that. If Nkrumah had flaws at all, on hindsight, he was the best for Ghana and the Black race.

By embracing Nkrumah fully in this timely renaming agenda, we don’t just rename an airport—we complete a chapter, fortifying our role in Africa’s awakening. The time is now: let’s finish what we started!

Editorial

Has Burkina Faso Began a Descent into Authoritarianism under Traore?

Something seismic has just happened in Burkina Faso—and Africa, and the world, should be paying close attention.

With the stroke of a decree approved by the council of ministers, the military-led government of President Ibrahim Traoré has dissolved all political parties and scrapped the legal framework governing their existence. Party offices, assets, structures—gone. Transferred to the state. Politics, as Burkina Faso has known it for decades, has been put on pause.

This is not administrative housekeeping.

This is a fundamental rewrite of the political order.

The government’s justification is blunt: political parties, it says, have become engines of division, corruption, and elite self-interest. Too many parties, too little nation-building. Too much competition for power, too little service to the people. The solution, in Traoré’s view, is unity before politics—a state rebuilt first, elections later.

It is a message that resonates far beyond Ouagadougou.

Across Africa, fatigue with multiparty democracy is real. For millions, democracy has meant elections without electricity, constitutions without jobs, and politicians who rotate offices while poverty stays put. Against that backdrop, some are asking an uncomfortable question: If democracy has not delivered, why defend it so fiercely?

But history demands honesty—and honesty complicates the applause.

Africa also knows this story well. The suspension of political parties has often been the opening chapter in longer, darker books: prolonged military rule, shrinking civic space, silenced dissent, and leaders who promise transition but grow comfortable with control. Coups, too, have a long and disappointing record. They rarely end as advertised.

And yet—this is where Burkina Faso unsettles easy conclusions.

Traoré is not governing like yesterday’s coup leaders. His administration has moved aggressively on national sovereignty: reclaiming control over resources, rejecting external political tutelage, pushing self-reliance, and speaking a language of dignity that resonates deeply with a generation raised on the failures of dependency. Crucially, many Burkinabè appear to be backing him—not out of fear, but belief.

This is what makes the moment dangerous and fascinating.

Is dissolving all political parties the first step toward authoritarian consolidation?

Or is it an audacious—if risky—attempt to reset a political system that many believe was never truly democratic to begin with?

From Accra to Addis Ababa, from Paris to Washington, observers will rush to label this move. But Burkina Faso is not a textbook case; it is a country at war with insurgency, burdened by history, and searching—desperately—for a model that works for itself.

Still, power without pluralism is power unchecked. And no matter how popular a leader may be today, the absence of political competition tomorrow raises a simple, enduring question: who watches the watcher?

Burkina Faso now stands at a fork in the road. One path leads to a genuine, time-bound reconstruction of the state, followed by a return to accountable civilian rule—stronger, leaner, and more rooted in the people. The other leads to a familiar African tragedy: revolutionary rhetoric giving way to permanent exception.

Which path Traoré chooses will define not just his legacy, but Burkina Faso’s place in Africa’s political future.

This is not a moment for blind praise or reflexive condemnation. It is a moment for vigilance, debate, and clear-eyed realism.

A reset may be necessary.

But history warns: when politics disappears, it rarely stays gone quietly.

The question now is not whether Burkina Faso has changed.

It has.

The question is whether this change will liberate the state—or outgrow the consent of its people.

Editorial

Trump Shrugs as the Dollar Slides — The World Shouldn’t

President Donald Trump’s casual dismissal of a sharp drop in the US dollar may play well to a domestic political gallery, but it should worry the rest of the world.

When the leader of the world’s largest economy signals comfort—even approval—with a weakening currency, markets listen. And they react.

On Tuesday, January 27, 2026, the US dollar recorded its steepest single-day fall since last year’s tariff-driven market turmoil, dropping as much as 1.2 percent. Asked whether he was concerned, Trump waved it off.

“The dollar’s doing great,” he said, pointing instead to business activity and trade. Investors, however, heard something else entirely: a green light to keep selling.

This matters because the dollar is not just another national currency. It is the backbone of the global financial system, involved in nearly 90 percent of all foreign exchange transactions worldwide. Its dominance underpins global trade, commodity pricing, sovereign debt markets, and central bank reserves. When confidence in the dollar weakens, the shockwaves travel far beyond US borders.

Trump’s remarks did not occur in a vacuum. The dollar has been under pressure for months, weighed down by policy uncertainty, renewed tariff threats, and persistent political pressure on the US Federal Reserve. Add to that the administration’s unpredictable foreign policy signals—from aggressive trade posturing to controversial geopolitical ambitions—and investors are increasingly questioning the long-term stability of US economic stewardship.

For emerging and developing economies, including Ghana, the implications are complex. On one hand, a weaker dollar can ease the burden of dollar-denominated debt and reduce the cost of imports priced in US currency. On the other, sharp or disorderly dollar declines can trigger global market volatility, disrupt capital flows, and unsettle export competitiveness. Financial instability rarely respects borders.

There is also a deeper concern: credibility. Reserve currencies rely as much on trust as on economic size. When political leaders appear indifferent to currency stability—or worse, view depreciation as a strategic tool—they risk undermining that trust. History shows that once confidence erodes, it is difficult to restore.

Trump’s relaxed tone may reflect a belief that a cheaper dollar boosts US exports and domestic manufacturing. But global finance is not a zero-sum game played on soundbites. Sudden or sustained dollar weakness can ripple through stocks, bonds, credit markets, and commodities, amplifying risks at a time when the global economy is already navigating fragile recoveries, geopolitical tension, and high debt levels.

For policymakers outside the United States, the lesson is clear: diversify risk, strengthen regional trade, and reduce overdependence on any single currency system. For investors, vigilance is essential. And for Washington, a reminder is overdue—the privilege of issuing the world’s dominant currency comes with responsibilities, not just political convenience.

The dollar’s slide may not yet signal the end of its dominance. But complacency from the White House is hardly reassuring. When the anchor of global finance starts to drift, the world cannot afford a captain who shrugs.

-

News14 hours ago

News14 hours agoGhana Gears Up for Vibrant 69th Independence Day Celebrations: Parades, Plays, Poetry, and Heritage in Focus

-

Tourism12 hours ago

Tourism12 hours agoEmirates Resumes Limited Flights from Dubai as Middle East Airspace Slowly Reopens Amid Ongoing Conflict

-

Ghana News15 hours ago

Ghana News15 hours agoNewspaper Headlines Today: Tuesday, March 3, 2026

-

Ghana News15 hours ago

Ghana News15 hours agoAyawaso East By-Election Results Trickle in, ECG Audits Fast-Reading Meters, and Other Trending Topics in Ghana (March 3, 2026)

-

Ghana News2 days ago

Ghana News2 days agoCourt Slaps Barker-Vormawor with GH₵5m for Defaming Kan Dapaah and Other Trending Topics in Ghana (March 2, 2026)

-

Fashion & Style5 hours ago

Fashion & Style5 hours agoThe New Wave of “Afro-Minimalism”: Redefining Luxury Beyond the Print

-

Ghana News5 hours ago

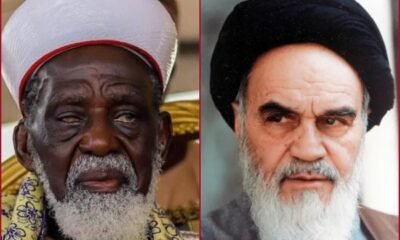

Ghana News5 hours agoGhana’s Top Muslim Leader Condemns Khamenei Assassination, Calls for New World Order Based on ‘Right Over Might’

-

Commentary12 hours ago

Commentary12 hours agoAt a glance: US‑Israel attack on Iran